“What’s the world for you if you can’t

make it up the way you want it?”

–Toni Morrison, Jazz

*

The attempts I made to get out of my own head were sundry and full of nonsense.

I visited a petting zoo for adults. I tried learning to meditate from a British computer voice. I stocked up on an unregulated nutrition powder called “Brain Dust.” My brain felt like dust. In the last few years, “dread for no reason” became one of my most frequent Google searches, as if the act of typing my feelings to a robot would make them go away. I gorged myself on podcasts about women who’d “snapped,” at once repulsed and tantalized by those who wore their madness on their sleeves. How good it must feel to “snap,” I thought.

My most cinematic attempt at mental rehab involved picking herbs on a farm in Sicily under a light-pollution-free sky. (“At night here, the stars are so close, they could fall into your mouth,” the herb farmer told me, sending my heart to my throat.) With varying degrees of “success,” I was doing everything I could think of to defect from the state of overwhelm and consumption that had become my life in the roaring 2020s. Anything to gain some perspective on the mental health exigency I’d been experiencing, and trying to rationalize, for the better part of a decade.

I had to understand how these mental magic tricks we play on ourselves combine with information overload like a chemistry experiment gone haywire.

Every generation has its own brand of crisis. Those of the 1960s and ’70s were about gaining freedom from physical tyrannies—equal rights and opportunities to vote, learn, work, mobilize. They were crises of the body. But as the century turned, so did our struggles inward. Paradoxically, the more collective progress we made, the more individual malaise we felt. Discourse about our mental unwellness crescendoed.

In 2017, Scientific American declared that the nation’s mental health had declined since the 1990s and that suicide rates were at a thirty-year high. Four years later, a CDC survey found that 42 percent of young people felt so sad or hopeless in the last two weeks that they couldn’t go about their normal days. The National Alliance on Mental Illness reported that between 2020 and 2021, crisis calls to their lifeline were up 251 percent.

We’re living in what they call the “Information Age,” but life only seems to be making less sense. We’re isolated, listless, burnt out on screens, cutting loved ones out like tumors in the spirit of “boundaries,” failing to understand other people’s choices or even our own. The machine is malfunctioning, and we’re trying to think our way out of it. In 1961, Marxist philosopher Frantz Fanon wrote, “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it or betray it.” Our mission, it seems, has to do with the mind.

My fixation with modern irrationality took root while I was writing a book about cults. It was 2020, and looking into the mechanics of cultlike influence during that year’s existential imbroglio cast new light on the many faces of twenty-first-century derangement. Since the new millennium, humanity had built a megamall full of fun and fresh ways to dissociate: Fringe conspiracy theories had gone mainstream. Celebrity worship reached a hallucinatory zenith. Disney Adults and MAGA zealots were blackout drunk on nostalgia, drowned in chimeras of the past. These misbeliefs came in a range of flavors, from whimsical to warlike, but one thing was certain—our shared grasp on reality had slipped.

The only explanation for this mass head trip that made any sense to me had to do with cognitive biases: self-deceptive thought patterns that developed due to our brains’ imperfect abilities to process information from the world around us. Social scientists have described hundreds of cognitive biases over the last century, though “confirmation bias” and the “sunk cost fallacy” were the two that came up most in my reporting.

Perusing just a few of these studies crystallized so much of the zeitgeist’s general illogic, like people with master’s degrees basing their social calendars on Mercury’s position in the cosmos, or our neighbors opting not to get vaccinated because a YouTuber in palazzo pants said it would “downgrade their DNA.” Cognitive biases also explained scads of my own irrationalities, personal choices I could never justify to myself, like the commitment in my early twenties to stick out a romantic relationship that I knew caused me suffering, or my tendency to engineer online enemies based on conflicts I’d invented. I needed to yank at that thread. I had to understand how these mental magic tricks we play on ourselves combine with information overload like a chemistry experiment gone haywire—Mentos and Diet Coke.

Our minds have been fooling themselves since the dawn of human decision making. The amount of input from the natural world alone was always too much for us to handle; cataloging the precise color and shape of every twig in order to understand it would take more than a lifetime. So, early brains came up with shortcuts that allowed us to make sense of our environment enough to survive it.

The mind has never been perfectly rational, but rather resource rational—aimed at reconciling our finite time, limited memory storage, and distinct craving for events to feel meaningful. Epochs later, the quantity of details to process and decisions to make has exploded like confetti, or shrapnel. We can’t hope to mull over every datapoint as deeply as we might like. So we tend to rely on our ancestors’ clever cheats, which come so naturally to us, we’re almost never aware of them.

Faced with a sudden glut of information, cognitive biases cause the modern mind to overthink and underthink the wrong things. We obsess unproductively over the same paranoias (Why did Instagram suggest I follow my toxic ex-boss? Does the universe hate me?), but we blitz past complex deliberations that deserve more care.

I have more than once experienced the disorientation of engaging in some battle of wits online, only to come up for air and feel in my body like I’d been using sparring tactics better suited to a Neolithic predator than a theoretical conversation. “I think because we have come so far technologically in the past 100 years, we think that everything is knowable. But that’s both so arrogant and so fucking boring,” said Jessica Grose, New York Times opinion columnist and author of Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood, in 2023. I’ve been referring to this era, when we’re so swiftly outpacing the psychological illusions that once served us, as the “Age of Magical Overthinking.”

While magical thinking is an age-old quirk, overthinking feels distinct to the modern era.

Broadly, magical thinking describes the belief that one’s internal thoughts can affect external events. One of my first exposures to the concept came from Joan Didion’s memoir The Year of Magical Thinking, which vivifies grief’s power to make even the most self-aware minds deceive themselves. Mythologizing the world as an attempt to “make sense” of it is a unique and curious human habit. In moments of fierce uncertainty, from the sudden death of a spouse to a high-stakes election season, otherwise “reasonable” brains start to buckle.

Whether it’s the conviction that one can “manifest” their way out of financial hardship, thwart the apocalypse by learning to can their own peaches, stave off cancer with positive vibes, or transform an abusive relationship to a glorious one with hope alone, magical thinking works in service of restoring agency. While magical thinking is an age-old quirk, overthinking feels distinct to the modern era—a product of our innate superstitions clashing with information overload, mass loneliness, and a capitalistic pressure to “know” everything under the sun.

In 2014, bell hooks said, “The most basic activism we can have in our lives is to live consciously in a nation living in fantasies….You will face reality, you will not delude yourself.” To become as aware as we can of the mind’s natural distortions, to see both the beauty and utter folly in them: This, I believe, ought to be part of our era’s shared mission. We can let the cognitive dissonance bring us to our knees, or we can board the dizzying swing between logos and pathos. We can strap in for a lifelong ride. Learning to stomach a sense of irresolution might be the only way to survive this crisis. That’s precisely what this exploration of cognitive biases has helped me do. Even more than Sicilian stargazing, writing this book has been the one thing that’s kept the buzz in my head at a decibel level I can stand.

The Zen Buddhists have a word, “koan,” which means “unsolvable riddle”: You break the mind in order to reveal deeper truths and reassemble the pieces to create something new. I wrote this book as a yearning, a Rorschach test, a PSA, and a love letter to the mind. It’s not a system of thought, but rather something more like a koan. If you have all but lost faith in others’ ability to reason, or have made a cornucopia of questionable judgments that you can’t even explain, my hope is for these chapters to make some sense of the senseless. To crack open a window in our minds, and let a warm breeze in. To help quiet the cacophony for a while, or even hear a melody in it.

__________________________________

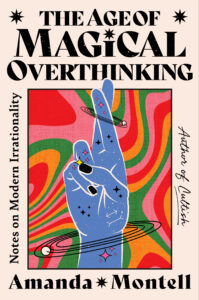

From The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern Irrationality by Amanda Montell. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.