The stand-up icon, who passed away at the age of 76 on Tuesday, was perhaps better than anyone else at mining personal torment for laughs

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73173804/RichardLewisObit_Getty_Ringer.0.jpg)

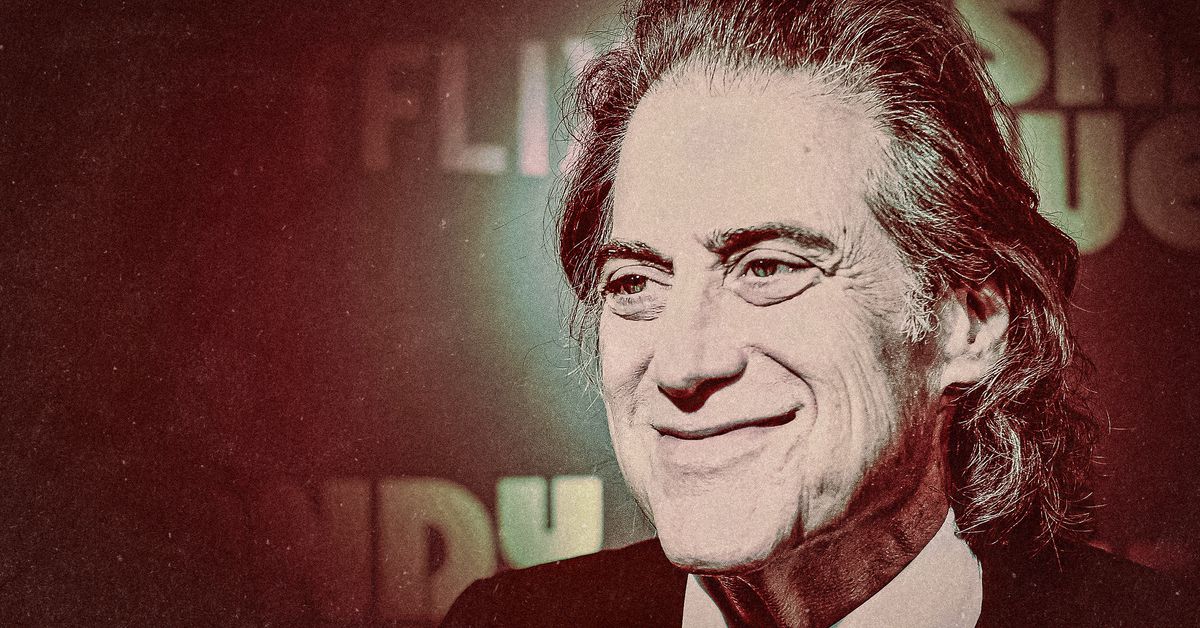

Getty Images/Ringer illustration

Richard Lewis wasn’t the first neurotic stand-up comic, but he was one of the best—and, as contradictory as it sounds, probably the most comfortable. “When I’m on stage, I’m the happiest I could ever be,” he told me in 2022, during an interview about his friend Warren Zevon. “I’m just in touch with who I am, and want to express it. It’s just calm. It’s like the eye of a hurricane.”

Lewis, who died of a heart attack on Tuesday at 76, wasn’t being hyperbolic. Over the course of his career, he spoke and wrote candidly about his strained relationship with his parents, drug use, alcoholism, depression, body dysmorphia, the pain caused by multiple surgeries, and most recently, his experience with Parkinson’s disease. That the Jewish guy with the poofy mane of black (and eventually gray) hair withstood that barrage is both extraordinary and admirable. But what made the self-described “Prince of Pain” special wasn’t his tolerance for personal torment. It was his ability to spin angst into affability. Self-deprecating jokes poured out of Lewis, but the sweat of a desperate hack never did. After all, his act wasn’t a put-on. It was just him.

Lewis was a paranoid person: “On my stationary bike, I have a rearview mirror,” he once quipped. His childhood was rough: when New York magazine asked him about his most memorable meal ever, he said, “It was in 1981—the first Thanksgiving I ever had without a social worker present.” And he always found himself in bad situations: in fact, Yale credited him with popularizing the phrase “the (blank) from hell” after his ’70s routine about a cursed date.

For the last 25 years, Lewis happily turned his inner turmoil outward as a recurring character on Curb Your Enthusiasm. In the HBO sitcom, now in its final season, he played an even more miserable version of himself opposite his real-life friend Larry David. Whenever Lewis popped up on Curb, something memorable happened. His delivery of the simplest lines were laugh-out-loud funny. Like when Larry dipped his nose into Lewis’s coffee in Season 10 and Lewis bellowed, “What are you, a fuckin’ goose?” Or when Lewis was shocked to find Larry selling cars at a dealership and shouted, “What are you, fuckin’ Willy Loman?” None of the show’s guest stars, it seemed, were better at breaking David. Often, when the two were meant to be arguing in a scene, you could tell how giddy they both were to be going back and forth with each other. “Richard and I were born three days apart in the same hospital and for most of my life he’s been like a brother to me,” David said in a statement on Wednesday. “He had that rare combination of being the funniest person and also the sweetest. But today he made me sob and for that I’ll never forgive him.”

Lewis was good at making other comics laugh. He was a regular on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, The Howard Stern Show, Late Night With Conan O’Brien, and The Daily Show. He was also one of David Letterman’s favorite guests, appearing on Late Night 48 times. To Lewis, Letterman’s support was a miracle. But it made sense. “It was just an amazing break for me that he understood me,” Lewis told me. “I bring that up because I’m so self-deprecating, and so is David. He’s so hard on himself.”

Lewis’s late-night ubiquity and his first two stand-up specials, I’m in Pain and I’m Exhausted, combined to help make him famous. By 1989, he was costarring in a sitcom with Jamie Lee Curtis called Anything but Love, a will-they-or-won’t-they rom-com that ran for four seasons on ABC, in which Lewis played a magazine columnist named Marty Gold. The fact that an anxious comedian could carry a hit show about a journalist is a bitterly hilarious reminder of the hold both of those professions used to have on America. It’s also proof of how likable Lewis was, even when he wasn’t spilling his guts in a comedy club.

I was too young for his comedy back in the early ’90s, but I remember seeing Lewis in commercials for one of the decade’s strangest products: BoKu, a juice box … but for grown-ups. In the long-running campaign, the eternally black-clad comedian basically just did his stand-up act, simply holding one of the soft drinks in his hand for 30 seconds at a time. When I interviewed him, he said that he had a hand in writing the ads—and he had a ball doing it. Leave it to Richard Lewis, the only man who could sell non-alcoholic juice boxes to adults.

Lewis could relate to people who’d gone through hell. Listening to him talk about Zevon, it was obvious that he revered the musician, and obvious why. “Some of the songs were very self-deprecating,” he said. “He was an exquisite writer.”

“A couple years before I bottomed out and got sober, I remember I was at the Palm restaurant in L.A., and there was a great table of a lot of rockers,” Lewis continued. “Warren was there, and I had never met him before. I wasn’t at the dinner, I was just wandering around the restaurant. It was about six guys, and I knew most of the table. But when I saw Zevon, I was just thrilled that I had the chance to just tell him what I thought about him.”

It turned out that Lewis and Zevon were practically neighbors. They even shopped at the same expensive Laurel Canyon grocer. “I loved it when I ran into him at the store buying $20 granola,” Lewis said. “I would walk around with my cart with him, and try to keep him there as long as possible. When I would make him laugh, I could see his face. He would laugh so loudly, but he took that first one or two seconds to breathe and take it in. Then he just let it out. It was like he really appreciated funny. I knew that, as a friend. Of course I loved that he admired me. You feel like a million bucks.”

Toward the end of Zevon’s life, when he had cancer and had fallen back into his old habits, he stopped talking to Lewis. It was the singer’s way of protecting his friend. “Because he knew I was sober …” Lewis said. “He was a tough guy, but that was what he did to me, and I understood it, and I loved him for it. I didn’t want to force the issue and call him. I did email him, though, and tell him what I thought about him, and that I understood, and that I loved him.”

Lewis compared Zevon to someone else he’d gotten to know in New York. “I used to hang out at Mickey Mantle’s bar and restaurant,” Lewis said. “It was near my hotel in Central Park South. Mantle and I were both alcoholics. I would often times bring my work with me and sit at the bar or in a booth, and go over concert material for hours and drink. He really dug me, Mantle. He had two pictures of me hanging. I say this with a great deal of pride: I was the only non-sports figure to be in that restaurant. There were hundreds of pictures of ballplayers, and me. What’s wrong with this fucking picture? It was crazy.”

Lewis recalls watching Bob Costas’s emotional TV interview with Mantle. It was 1994, about a year before the Yankees great died of liver cancer. The Hall of Famer spoke openly about his alcoholism and failings as a parent. “Here’s the guy going out and wanting to tell people that he might have been worshiped,” Lewis said, “but he could have lived his life a much better and a much healthier way.” That summer, Lewis told me, “I got sober.”

As permanently anguished as he was, Lewis knew he was fortunate to have an outlet for his pain. It’d be a cliché to say that comedy saved him, but it did seem to keep him going until the very end. In the face of a Parkinson’s diagnosis, he returned for the final season of Curb. In last week’s “Vertical Drop, Horizontal Tug,” Larry and Lewis are in the middle of a golf round when Lewis tells Larry that he’s putting him in his will. Larry, of course, is mad about it. He doesn’t need his friend’s money. He says he’ll just donate it to charity. The incredulity, of course, leads to another delightfully familiar argument.

“I’m giving it to you anyway, pal,” Lewis says.

“Oh my God, fuck you,” Larry replies.

That was Lewis. Even when life was cursing him out, he refused to give up.