Books and looks: gen Z is ‘rediscovering’ the public library

Young people are using the hallowed institutions at higher rates than older generations. And they’re not just there to read

Henry Earls dresses up to go to the library. He’ll plan outfits after searching “dark academic” on Pinterest, taking inspiration from the internet subculture obsessed with higher education and literature. He picks out cozy knitted sweaters and accessorizes with well-worn copies of classic books. Earls looks like an adjunct English professor – or an extra in Saltburn.

“I want to cultivate an aesthetic when I go to the library,” the 20 year-old Cooper Union art student said. “And, honestly, I dress up to see if someone will come up to me and say hi.”

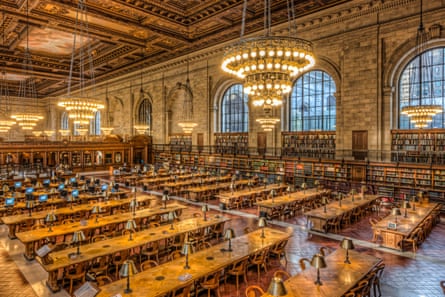

When Earls isn’t studying at the New York Public Library, he cruises the reading room for friends – or more than friends. Last week, he (respectfully) slipped his number to a young woman sitting near him, which led to a flirty text exchange. A few days ago, he made a friend on the library steps, a law student prepping for an exam.

“We met in an environment that supports focus and growth, so we hit it off,” Earls said. “He might come hang out with my friends and me sometime.”

Gen Z seems to love public libraries. A November report from the American Library Association (ALA) drawing from ethnographic research and a 2022 survey found that gen Z and millennials are using public libraries, both in person and digitally, at higher rates than older generations.

More than half of the survey’s 2,075 respondents had visited a physical library within the past 12 months. Not all of them were bookworms: according to the report, 43% of gen Z and millennials don’t identify as readers – but about half of those non-readers still visited their local library in the past year. Black gen Zers and millennials visit libraries at particularly high rates.

Libraries have never been just about books. These are community hubs, places to connect and discover. For an extremely online generation that’s nearly synonymous with the so-called “loneliness epidemic” libraries are increasingly social spaces, too.

“We traditionally think of libraries as very quiet, and parts of them are, but what we observed watching gen Z in libraries is that there are some really great spaces for teens, big rooms where they can do things like gaming or making their own music,” said Rachel Noorda, a co-author of the ALA report. “It’s a place to be solitary, but also a place to build community.”

And a place to flex. On TikTok, Earls posts selfie videos showing him studying, journaling or reading in front of the Bryant Park library’s breathtaking beaux-arts backdrop. The clips get millions of views. “I think people my age are craving something more authentic, and looking for something that’s real,” Earls said. “What’s more real than books and physical material?”

Library-related content does well on #booktok, where young literary influencers – many of them still in high school – drive sales by recommending and reviewing stories. (Colleen Hoover, #booktok’s favorite author, shot to the top of bestseller lists due to viral endorsements; other recommended books often fall into the “romantasy” young adult category.)

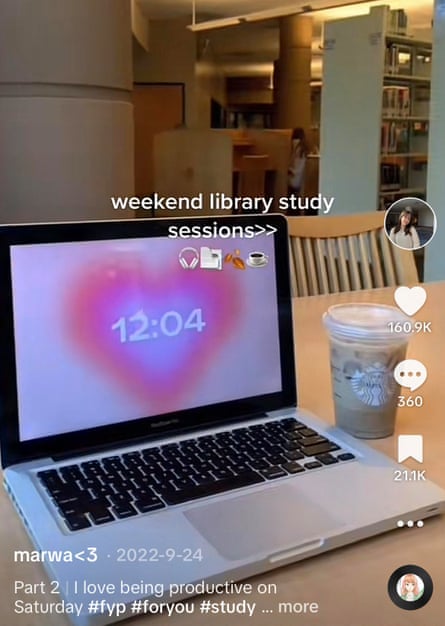

“A lot of my followers find libraries appealing in an aesthetic way,” said Marwa Medjahed, an 18-year-old TikToker who posts about life as a George Washington University freshman to her 115,000 followers. “They feel like I’m enjoying studying, rather than being in a bleak dorm room with harsh lighting.”

While many young people read digitally, downloading (or pirating) titles, hard copies of books are fetishized on social media. “Ebooks don’t make good props on TikTok,” Kathi Inman Berens, co-author of the ALA report, said. “You need book materiality, a printed book, something that helps visually.” Why buy the title when you can just borrow it at the library?

Tom Worcester, 28, is one of the co-founders of Reading Rhythms, a New York-based “reading party” held at bars. Attendees pay $20 to cozy up with their books while DJs play ambient tracks in the background. Guests can mingle in between sets. The events are held twice weekly, but that doesn’t stop Worcester from going to real libraries, too. “If I know I have a good four-hour block of time to myself, I’ll ask a bunch of friends, ‘Do you want to go to the library today?’” he said. “I make it a social event.”

At the end of last year, Worcester and a friend took a trip to Amsterdam, where they visited the Openbare Bibliotheek. Inside the second-largest library in Europe, the pair conducted personal “annual reviews”, spending hours reflecting on the highs and lows of their year. “When you’re at the library, there’s an unspoken agreement that you will focus on what you have to do,” he said.

Talk to any young and online person long enough about libraries and they’ll inevitably bring up the “third place”, a term coined in 1989 by the urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg. Like attachment styles or imposter syndrome, the third place is an academic term turned social media discourse point. Separate from home and work, it is a space for gathering and socialization. Bars, coffee shops, churches and libraries are the usual examples.

Gen Z’s well aware that they lack many of the third places their parents had, especially as the lines between work and home blurred during Covid. Libraries are the last place they feel exists that asks nothing of them. You can truly come as you are.

“Coffee shops get so crowded, and you have to spend money to be there, but libraries are open for everyone,” said Anika Neumeyer, a 19 year-old English student who volunteers at the Seattle Public Library. “There’s a lot less pressure to be doing something in the public library. No one’s going to judge you.”

In 2018, the librarian and academic Fobazi Ettarh coined the term “vocational awe”. It describes the idea that libraries are “inherently good” and “beyond critique”, which can lead to the exploitation of their workers. Abby Hargreaves, a librarian in the Washington DC area who posts about her job to 48,000 TikTok followers, believes gen Z has a tendency to romanticize the position.

“There’s this idea of, ‘I’ll go to my library and have some great adventure while I’m there,’” Hargreaves said. “But then we also see people who are looking to tear libraries down, whether that’s through budget cuts or legislated book bans.”

If gen Z is going to save libraries, they couldn’t pick a better time to advocate for them: across the country, these institutions and their workers are under attack. Last year, Mayor Eric Adams of New York City slashed funding to public libraries, cutting Sunday service in the five boroughs – and drawing the ire of Cardi B, who went on an Instagram Live tirade over the news.

A series of library-related bills are making their way through Idaho’s legislature that would restrict material it deems inappropriate for minors and allow family members to file $2,500 lawsuits against libraries that violate the law. Last year, Missouri Republicans attempted to strip all state funding from public libraries. This week, Chaya Raichik, the rightwing influencer behind Libs of Tiktok, was appointed to a library advisory position for Oklahoma’s schools, which means she could help determine what books are “appropriate” for students.

Meanwhile, school librarians in states across the country report enduring harassment – and for some, death threats – by rightwing trolls just for doing their jobs.

“It’s so strange when you hear, ‘Oh, gen Z loves libraries,’ or when the algorithm keeps feeding you videos of beautiful libraries, but then there’s no more Sunday service and you have to wait weeks for your book to come,” said Anna Murphy, an upper school librarian at the Berkeley Carroll School in Brooklyn. “The library love and hate seems to exist in two different universes.”

Emily Drabinski, president of the ALA, reminds us that the vast majority of US voters oppose book bans and hold librarians in “high regard”. “Most people love the library, especially after 50 years of systematic disinvestment of public institutions, since it’s the only one left standing,” she said.

Arlo Platt Zolov is a 15-year-old who lives in Brooklyn and has what must be one of the all-time-best after-school jobs: running the information desk at the central branch of the public library, steps away from Prospect Park. “A lot of people my age are surrounded by tech and everything’s moving so quickly,” he said. “Part of me thinks we’re rediscovering libraries not as something new, but for what they’ve always been: a shared space of comfort.”