Money for art-making comes in many forms, and unfortunately there never seems to be enough of it to meet every artist’s brilliantly ambitious ideas.

Right now, after the chaos of the COVID years and amid a cost of living crisis, many in the sector are feeling like arts funding is at an all-time low… Or is it?

While the feeling on the ground is that public arts funding is scarce, when you study the data, things aren’t quite as bad as they seem (though they aren’t all that great either!).

Shifts in arts spending across three levels of government

The first important caveat to put around any talk of government arts funding is that the level of support differs widely depending on the art form you are in.

According to independent arts think-tank A New Approach (ANA) in its recent Big Picture 4 report, funding for arts and culture across all three tiers of government is far from evenly split.

For example, the Film, Radio and Television sector typically receives 90% of its government funding from the Federal Government, while 60% of the Museums, Archives, Libraries and Heritage sector’s funding comes from state and territory governments.

When it comes to the all-important Arts category – which includes performing arts, visual arts and crafts, music, design, community arts and cultural development, writing and publishing and arts festivals – ANA’s report shows around 70% of these art forms’ government funding comes from state governments – which is a surprisingly high percentage.

Read: What a $20 million lifeline for Sydney’s cultural life buys

But importantly (and as the ANA’s report openly points out), these figures can be deceiving because they include government money spent on capital works and arts infrastructure, so not all of it goes directly to arts activities or artists’ projects.

In fact, if a state or territory government has a major new museum or gallery build underway, or when it has to carry out maintenance work to keep ailing cultural buildings in working order, the money left over to fund artists’ activities and projects can look tiny by comparison.

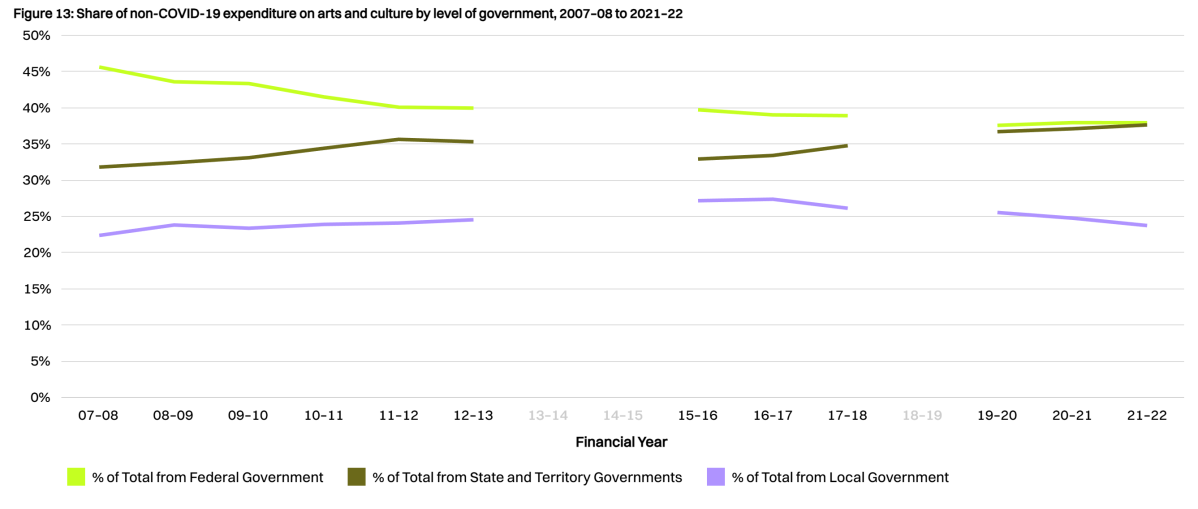

That aside, the ANA’s report shows how, looking at all art forms combined, the federal-state-local Government funding split has been shifting, with state and territory governments almost overtaking the Federal Government in their rate of public arts spending.

Historically, the Federal Government has been the biggest spender on arts activities, accounting for around 40% of total government arts funding since 2010. The state and territory governments arts spending is close behind, accounting for around 35% of the total, while local governments contribute around 25%.

But in 2021-22, state and territory governments’ year-on-year investment rose slightly – from 36% to 38% – while the Federal Government spend remained steady at 38%.

At first glance, these proportional changes seem slight, but when you take a longer range view and look at the data since 2007, you realise that state government arts spending is trending distinctly upwards, while Federal arts spending is going exactly the opposite way and is potentially flat lining at a new (lower) proportional rate.

The implications for these funding split trends get interesting when you consider the different budget realities facing our eight states and territories from year to year (i.e some states and territories may be in long-term debt, while others enjoy surpluses based on their mineral exports and other factors).

So, will this increasing proportion of state government funding penalise artists in “poorer” states and territories over time?

At the present moment, the fairly even funding split between each level of government helps keep these adverse outcomes in the low-risk category, but this is surely a space to watch to ensure the current picture doesn’t climb any further out of balance and start to work against artists in the states and territories with limited spending capacities.

Why Federal arts funding matters so much

Putting aside the concern that, proportionally, Federal Government arts spending is in decline, ANA’s report also reveals that, when looking at the overall bigger picture, there is positive news to share.

According to ANA’s most recent data (taken from 2021-22), the total combined investment in arts and culture from all three tiers of government, including arts funding received from non-arts government arts departments, is up 4% in real terms (adjusting for inflation) on the previous year. This total combined government arts spend was approximately $7.7 billion in 2021-22 (up from $7.4 billion in 2020-21).

What’s more, this funding snapshot is based on 2022 data, before the Albanese Government released its National Cultural Policy Revive in February 2023. Notably, a key theme of Revive was an extra $200 million for the sector over the next four years.

However, when you compare this “once in a generation” Federal arts funding to the last game-changing arts policy moment in Australia – 30 years ago when Paul Keating’s Labor Government launched its own new national arts policy with its Creative Nation package – things start to look different.

When Paul Keating made his Creative Nation pledge in 1994, he injected an extra $252 million over four years into the arts. That means that, without even adjusting for inflation that decades-old funding pledge was still $52 million more than the Albanese Government pledged with its Revive package last year.

Comparing the figures in real terms shows how the Federal Government’s latest funding injection could be seen as a backwards step, because, once you do adjust for inflation, Revive’s funding increase would need to be around $541 million over four years (not $200 million) to match Creative Nation in ambition and value.

Read: Alarming cost increases for arts organisations not in line with funding levels

Another sign that Australian government arts spending across all three tiers of government is lagging in real terms can be found in ANA’s Big Picture 4 report, which shows how in the 15 years since 2007 Australia’s population has grown by 22%, while government arts spending has increased by only 14%, making per capita government arts investment $114 in 2021-22, compared to $144 per person in 2007-08.

Also, as reported recently by arts writer and journalist Alison Croggin in her long-form essay in The Monthly, when it comes to the fate of independent performing artists and small theatre companies competing for Federal Government funding, it seems this particular area of the arts has never been more neglected that it is right now.

Croggin describes how, last year, 64% of the Federal funding agency Creative Australia’s budget was spent on the 38 companies who make up the National Performing Arts Partnership Framework (NPAPF), leaving only 36% of its funds to spend on supporting other performing arts projects such as those by small-to-medium companies and independents.

This compares to the picture 14 years ago, when Creative Australia (then the Australia Council) funded 28 flagship performing arts companies through its Major Performing Arts (MPA) program with 41% of its total budget, leaving 59% to fund other performing arts projects.

This significant swing against the smaller players is a gut-punch for the independent performing arts sector and helps explain why so many independents are crying out for lifelines (or as Croggin aptly puts it, are in a state of ‘stage plight’).

Revenue from sales: yes, that’s important funding!

Finally (and if you have made it to this point in the article without losing too much hope) there is one other important arts money observation to make that points to bright sparks on the horizon.

We know that government funding is a very important piece of the overall arts money picture, helping to fund ambitious work and invest in jobs and services that ultimately see returns to government and taxpayers, but it is a total myth to say that the cultural and creative sector relies predominantly on government funding to survive.

As ANA’s Big Picture 4 report points out, ‘the largest single source of revenue for cultural and creative business [is] the sales of goods and services, including those not-for-profit organisations with a cultural purpose’.

According to research released by ANA last year, 87% of the arts sector’s overall revenue comes from sales of goods and services, with that overall figure including the whole gamut of arts enterprises in this country – from the commercially lucrative end of the market (such as creative IT services) to the not-for-profit arts companies that generate only around 27% of their income from sales (based on 2019-20 data).

ANA also noted that Australian consumers spent $45.6 billion in annual household expenditure on entertainment and recreation activities in 2021, which is an absolutely colossal figure, but is a bit misleading when you look at the broad range of activities (other than arts activities) included in the ‘arts and recreation’ category.

Nevertheless, it is vital to remember that artistic and creative pursuits can be profitable ventures, and Australians are generous supporters of artists’ work in their roles as consumers of art in its many forms.

So, while things may look bleak for many artists right now (yes, there is less cash around at the moment and people are staying home more than usual), over the long term, the evidence shows there is strong consumer demand for art and arts experiences in this country and, once you find your audience base, they will show up and keep investing in what you do.