May 2024 Issue

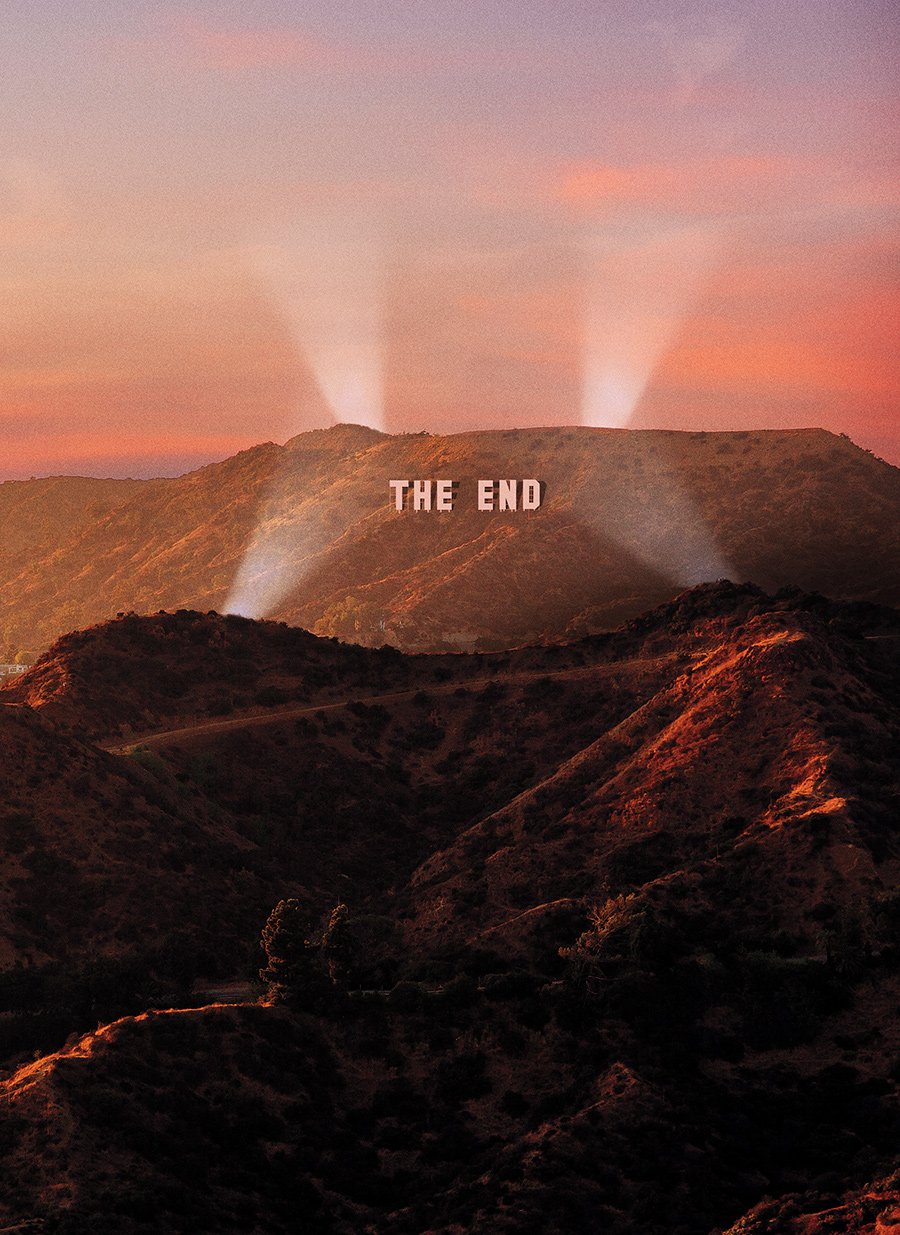

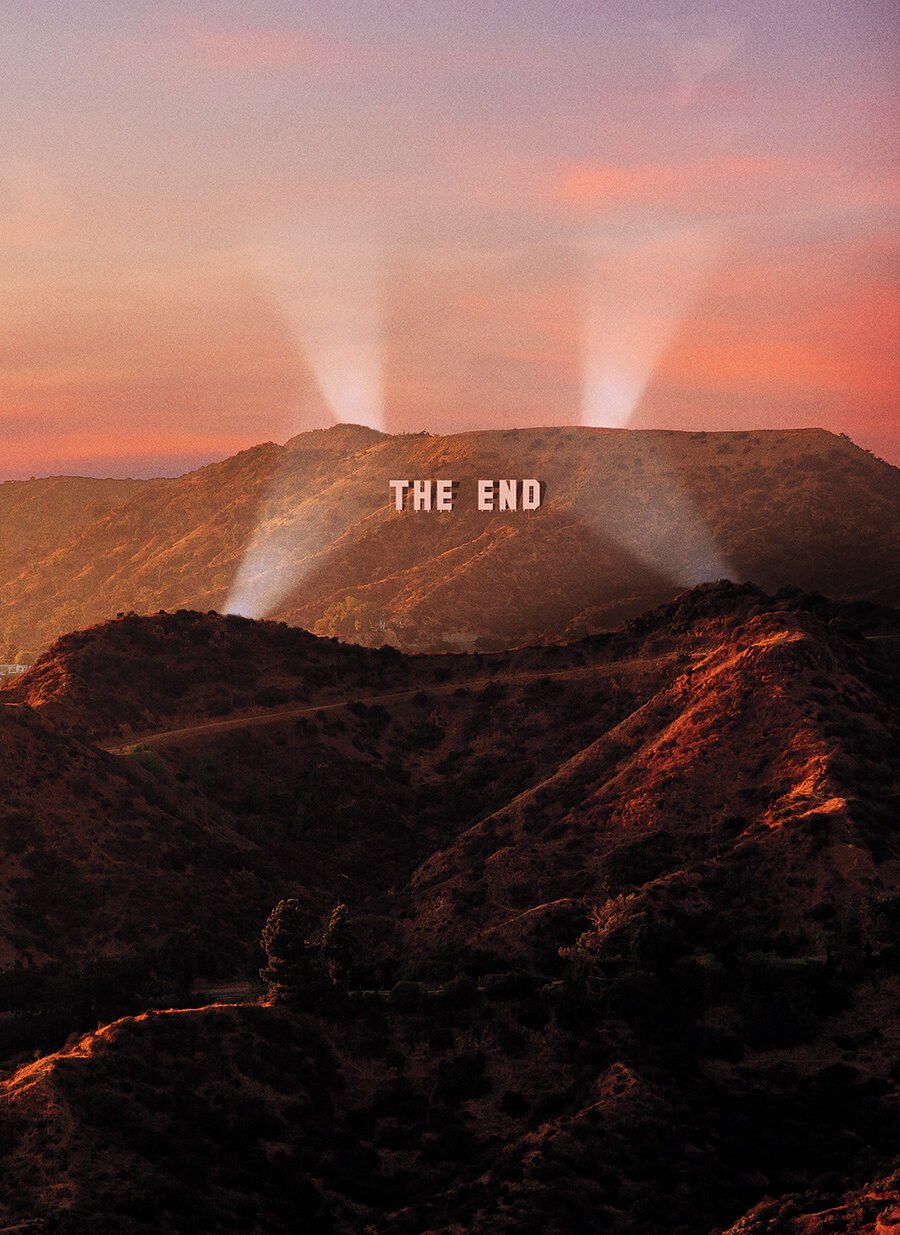

The Life and Death of Hollywood

Photo illustration by Nicolás Ortega

In 2012, at the age of thirty-two, the writer Alena Smith went West to Hollywood, like many before her. She arrived to a small apartment in Silver Lake, one block from the Vista Theatre—a single-screen Spanish Colonial Revival building that had opened in 1923, four years before the advent of sound in film.

Smith was looking for a job in television. She had an MFA from the Yale School of Drama, and had lived and worked as a playwright in New York City for years—two of her productions garnered positive reviews in the Times. But playwriting had begun to feel like a vanity project: to pay rent, she’d worked as a nanny, a transcriptionist, an administrative assistant, and more. There seemed to be no viable financial future in theater, nor in academia, the other world where she supposed she could make inroads.

For several years, her friends and colleagues had been absconding for Los Angeles, and were finding success. This was the second decade of prestige television: the era of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Homeland, Girls. TV had become a place for sharp wit, singular voices, people with vision—and they were getting paid. It took a year and a half, but Smith eventually landed a spot as a staff writer on HBO’s The Newsroom, and then as a story editor on Showtime’s The Affair in 2015.

I first spoke with Smith in August of last year, four months into the strike called by the Writers Guild of America against the members of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the biggest Hollywood studios. In 2013, she’d begun to develop the idea for what would become Dickinson, a gothic, at times surreal comedy based on the life of the poet, Emily. “I realized you could do one of those visceral, sexy, dangerous half hours but make it a period piece,” she said. “I was never trying to write some middle-of-the-road thing.” She sold the pilot and a plan for at least three seasons to Apple in 2017; she would be the showrunner, and the series had the potential to become one of the flagship offerings of the company’s streaming service, which had not yet launched.

Looking back, Smith sometimes marvels that Dickinson was made at all. “It centers an unapologetic, queer female lead,” she said. “It’s about a poet and features her poetry in every episode—hard-to-understand poetry. It has a high barrier of entry.” But that was the time. Apple, like other streamers, was looking to make a splash. “I mean, they made a show out of I Love Dick,” Smith said, referring to the small-press cult classic by Chris Kraus, adapted into a 2016 series for Amazon Prime Video. “That doesn’t happen because people are using profit as their bottom line.”

In fact, they weren’t. The streaming model was based on bringing in subscribers—grabbing as much of the market as possible—rather than on earning revenue from individual shows. And big swings brought in new viewers. “It’s like a whole world of intellectuals and artists got a multibillion-dollar grant from the tech world,” Smith said. “But we mistook that, and were frankly actively gaslit into thinking that that was because they cared about art.”

Making a show for Apple was not what she’d hoped it would be. What the company wanted from her and the series never felt clear—there was a “radical information asymmetry,” she said, regarding management’s priorities and metrics. After she and her colleagues completed the first season of Dickinson, they waited for the streamer to launch and the show to air. Their requests for a firm timeline and premiere date were ignored. Smith started to worry that Apple might scrap the idea for the streaming platform altogether, in which case the show might never be seen, or might even disappear—she didn’t have a copy of the finished product. It belonged to Apple and lived on the company’s servers.

“It was communicated to me,” Smith said, “that my only choice to keep the show alive was to begin all over again and write a whole new season without a green-light guarantee. So I was expected to take on that risk, when the entities that stood to profit the most from the success of my creative labor, the platform and studio, would not risk a dime.” “It was also on me,” she went on, “to kind of fluff everybody involved in the entire making of the show, from the stars to the line producer to the costume designer, etcetera, to make them believe that we’d be coming back again and prevent them, sometimes unsuccessfully, from taking other jobs.”

Finally, in late 2019, when Smith and her colleagues were two months into production on Season 2, the show premiered as one of the streamer’s four original series. It was an immediate critical success and a sensation on social media. “In Apple TV+’s initial smattering of shows,” wrote the Washington Post, “only ‘Dickinson’ is a delicious surprise.” It received a 2019 Peabody Award; in 2021 it made the New York Times’ list of best programs of the year and won a Rotten Tomatoes prize for Fan Favorite TV Series.

But Smith was losing steam. “I was only allowed to make the show to the extent that I was willing to take on unbelievable amounts of risk and labor on my own body perpetually, without ceasing, for years,” she said. “And I knew that if I ever stopped, the show would die.” It had seemed to her that Apple didn’t value the series, and she felt at a loss. Smith now knows that Dickinson was the company’s most-watched show in its second and third seasons. But at the time, she had no access to concrete information about its performance. As was the habit among streamers, Apple didn’t share viewership data with its writers. And without that data, Smith had no leverage. In 2020, after three seasons, she told Apple that she was done. “I said, I can’t do it anymore. And Apple said, Okay.”

“Passion can only get you so far,” she told me. But she’d stayed in Hollywood. “I’m an artist,” she said, “and I’m never going to stop creating.” The industry was still the only place one could make a real living as a writer. “When people say, Why stay in TV?” she said, “The answer is, There is nothing else. What do you mean?”

The truth was that the forces that had opened doors for Smith were the same ones that had made her individual work seem not to matter. They were the same forces that had been degrading writers’ working lives for some time, and they were cannibalizing the business of Hollywood itself.

Thanks to decades of deregulation and a gush of speculative cash that first hit the industry in the late Aughts, while prestige TV was climbing the rungs of the culture, massive entertainment and media corporations had been swallowing what few smaller companies remained, and financial firms had been infiltrating the business, moving to reduce risk and maximize efficiency at all costs, exhausting writers in evermore unstable conditions.

“The industry is in a deep and existential crisis,” the head of a midsize studio told me in early August.* We were in the lounge of the Soho House in West Hollywood. “It is probably the deepest and most existential crisis it’s ever been in. The writers are losing out. The middle layer of craftsmen are losing out. The top end of the talent are making more money than they ever have, but the nuts-and-bolts people who make the industry go round are losing out dramatically.”

Hollywood had become a winner-takes-all economy. As of 2021, CEOs at the majority of the largest companies and conglomerates in the industry drew salaries between two hundred and three thousand times greater than those of median employees. And while writer-producer royalty such as Shonda Rhimes and Ryan Murphy had in recent years signed deals reportedly worth hundreds of millions of dollars, and a slightly larger group of A-list writers, such as Smith, had carved out comfortable or middle-class lives, many more were working in bare-bones, short-term writers’ rooms, often between stints in the service industry, without much hope for more steady work. As of early 2023, among those lucky enough to be employed, the median TV writer-producer was making 23 percent less a week, in real dollars, than their peers a decade before. Total earnings for feature-film writers had dropped nearly 20 percent between 2019 and 2021.

Writers had been squeezed by the studios many times in the past, but never this far. And when the WGA went on strike last spring, they were historically unified: more guild members than ever before turned out for the vote to authorize, and 97.9 percent voted in favor. After five months, the writers were said to have won: they gained a new residuals model for streaming, new minimum lengths of employment for TV, and more guaranteed paid work on feature-film screenplays, among other protections.

But the business of Hollywood had undergone a foundational change. The new effective bosses of the industry—colossal conglomerates, asset-management companies, and private-equity firms—had not been simply pushing workers too hard and grabbing more than their fair share of the profits. They had been stripping value from the production system like copper pipes from a house—threatening the sustainability of the studios themselves. Today’s business side does not have a necessary vested interest in “the business”—in the health of what we think of as Hollywood, a place and system in which creativity is exchanged for capital. The union wins did not begin to address this fundamental problem.

Currently, the machine is sputtering, running on fumes. According to research by Bloomberg, in 2013 the largest companies in film and television were more than $20 billion in the black; by 2022, that number had fallen by roughly half. From 2021 to 2022, revenue growth for the industry dropped by almost 50 percent. At U.S. box offices, by the end of last year, revenue was down 22 percent from 2019. Experts estimate that cable-television revenue has fallen 40 percent since 2015. Streaming has rarely been profitable at all. Until very recently, Netflix was the sole platform to make money; among the other companies with streaming services, only Warner Bros. Discovery’s platforms may have eked out a profit last year. And now the streaming gold rush—the era that made Dickinson—is over. In the spring of 2022, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates after years of nearly free credit, and at roughly the same time, Wall Street began calling in the streamers’ bets. The stock prices of nearly all the major companies with streaming platforms took precipitous falls, and none have rebounded to their prior valuation.

The industry as a whole is now facing a broad contraction. Between August 2022 and the end of last year, employment fell by 26 percent—more than one job gone in every four. Layoffs hit Warner Bros. Discovery, Netflix, Paramount Global, Roku, and others in 2022. In 2023, firings swept through the representation giants United Talent Agency and Creative Artists Agency; Netflix, Paramount Global, and Roku again; plus Hulu, NBCUniversal, and Lionsgate. In early 2024, it was announced that Amazon was cutting hundreds of jobs from its Prime Video and Amazon MGM Studios divisions. In February, Paramount Global laid off roughly eight hundred people. It’s unclear which streamers will survive. As James Dolan, the interim executive chair of AMC Networks, told employees in late 2022 as he delivered news of massive layoffs—roughly 1,700 people (20 percent of U.S. staff) would lose their jobs—“the mechanisms for the monetization of content are in disarray.”

Profit will of course find a way; there will always be shit to watch. But without radical intervention, whether by the government or the workers, the industry will become unrecognizable. And the writing trade—the kind where one actually earns a living—will be obliterated.

Greed is not new to Hollywood. The well-off career we associate with twentieth-century screenwriting came about from a combination of worker action and federal regulation. The job was shaped in its early years, beginning in the Twenties, by a cartel of major motion-picture companies that, in 1948, would be found by the Supreme Court to have conspired to fix prices and monopolize the industry. Yet writing for the studios was good, salaried work. Up until the brink of the Depression, the companies were rolling in money. In 1931, average yearly income for a full-time, regularly employed writer was more than $14,000—roughly $273,000 in today’s money—more than three times that of the average American.

But in 1933, both MGM and Paramount Pictures cut screenwriters’ pay by 50 percent, and writers moved to form a union. The Screen Writers Guild was certified in 1938, and its first contract, in 1942, secured a guaranteed baseline pay of $125 a week—the equivalent of roughly $2,500 today—and the power to arbitrate over screenwriting credits, which had previously been at the whim of producers.

When the Supreme Court ruling came down, studio power was dealt another blow. The industry’s eight reigning companies were each forced to enter into an agreement with the Department of Justice, collectively known as the Paramount Decrees, which prohibited them from both distributing and exhibiting the films they produced—they could do only one or the other. The companies that owned theater chains gave up their cinemas, taking a significant hit. In the years that followed, the studios, less flush with cash, began to prefer freelance writers to salaried employees.

By the end of the Fifties, when 86 percent of Americans owned a television, writers had piecemeal established limited residual payments but wanted more. The studios—which now made both films and television—claimed that the fast-changing business was too uncertain to increase writers’ cuts, an assertion that, according to the film and media historian Miranda Banks, later executives would repeat with each major technological innovation in distribution, from cable to VHS tapes to DVDs, and finally to streaming. In 1960, the union, now the Writers Guild of America, went on strike, soon followed by the Screen Actors Guild. Both won expanded residuals, increased minimums, pensions, and health benefits. Most writers were now freelancers, but they had established a basis for long and stable careers.

Over the next two decades, the writing profession was further bolstered by a federal government that enforced and expanded antitrust law. In 1970, the Federal Communications Commission instituted the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules—or Fin-Syn—which barred networks from holding ownership stakes in the prime-time and syndicated programs that they aired, effectively prohibiting film studios from owning TV networks and vice versa, and generally increasing competition. In the mid-Seventies, full-time TV staffers were paid a minimum of roughly $30,000 a year, almost twice the median family income in 1976. For high-budget feature-film screenplays, writers made a baseline of about $17,000, or around $95,000 in today’s money.

It wasn’t until the early Eighties, when the Reagan Revolution hit Hollywood, that the guardrails began to fall. In 1983, the Department of Justice allowed HBO, Columbia Pictures, and CBS to merge to form TriStar Pictures, combining cable, film, and broadcast-network interests in direct violation of antitrust law. Executives at other entertainment companies took note and moved to create their own conglomerates. In 1985, the DOJ went a step further, issuing a memo, later discovered by the historian Jennifer Holt, stating that it would no longer enforce the Paramount Decrees, and the studios scooped up theater chains once again. When the Clinton Administration came to power, it carried on what its Republican predecessors had begun. In 1993, the FCC began to formally repeal the Fin-Syn rules, and in 1996, Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act, which removed restrictions on the cross-ownership of broadcast networks and cable providers. In 1994, in an unprecedented deal, cable giant Viacom merged with retailer Blockbuster Video, and took over Paramount Pictures. In 1996, Disney merged with Capital Cities/ABC to become the largest entertainment conglomerate in the world. The next year, Time Warner—already the product of two massive corporations, and previously the biggest conglomerate—joined with Turner Broadcasting System and reclaimed the crown. The gates had been opened, and the new monopolization was only just beginning.

At first, deregulation did not seem to harm writers. The mergers and acquisitions opened up synergies across the newly diverse properties within each conglomerate, bringing in, according to the historian of Hollywood Tom Schatz, unprecedented profits. This coincided with a boom in the theatrical business and may have contributed to increasing movie budgets—which skyrocketed during the Eighties and Nineties—and increased pay for screenwriters. In the late Eighties and throughout the Nineties, executives seemed to have more money to spend than ever before. Studios were hungry for original material, and invested more in development. They paid writers to try out concepts, crack stories, and see what worked. Howard A. Rodman, a writer for the recent HBO series The Idol and a former president of the WGA West, had started out in 1987. “In the era that I came up in,” he told me in August, “a studio might develop thirty to forty screenplays to get the one that actually sang.” The norm was what’s known as a multistep deal: studios paid up front for ideas, then scripts, then rewrites. Robin Swicord, writer of the adaptations for 1994’s Little Women and 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, told me: “When you would walk into someone’s office for a meeting, you’d see behind them a wall of screenplays.” She worked with one executive who oversaw 120 scripts in development in one year.

There was a heightened interest in “spec” scripts—unsolicited screenplays—and doors seemed to fly open. The writer John Brancato had vaulted into the A-list in 1991, when he sold the script that would later become The Game, starring Michael Douglas. A year or two later, he told me, he was hired to write a major movie screenplay—what eventually became The Net, starring Sandra Bullock—based on only a vague conversation. Pay ranged from solid to life-changing. In 1994 and 1995, original scripts for high-budget movies brought in a minimum of around $72,000—the equivalent of about $150,000 today.

In television, deregulation had aided the rise of cable, opening up new opportunities for writers. In the mid-Eighties, there had been fewer than fifty cable networks; by the end of the Nineties, there were more than two hundred, and nearly 70 percent of American homes had access. Multiple series from HBO, such as Sex and the City, which first aired in 1998, and The Sopranos, which debuted in 1999, were not only hits but cultural phenomena, and other cable networks dove in to scripted content.

A staff writer on a premium cable show in 1998 working for five months would make at least $2,400 a week—adding up to more than $90,000 in today’s money. Writers above the entry level would receive lump sums of more than $17,000 for authoring complete episodes. They also earned residuals. Broadcast networks often paid writers even more than cable, and writers were usually employed for longer. In September, I spoke with an A-list film and TV writer who worked on a variety of network shows in the late Nineties and early Aughts. “You felt like you hit the majors,” he said. “You were on call twenty-four seven; you worked nights. But the given was that you’re getting paid a gazillion dollars. It was an amazing time to be a television writer.”

Behind the scenes, however, deregulation was already allowing executives to shore up extraordinary power, and a new distance was forming between business interests and the production of film and TV. Writers’ fortunes were set to change.

By the early Aughts, six enormous conglomerates—Disney, General Electric, News Corporation, Sony, Time Warner, and Viacom—controlled every major movie studio and broadcast network, and a substantial portion of the profitable cable businesses. The conglomerates were raking in more than 85 percent of all film revenue and producing more than 80 percent of American prime-time television. As these entities grew, business operations became much more complex, and the sleight of hand known as Hollywood accounting—obfuscating exactly how much is spent and earned, exactly how much is due to be paid out—became much easier for the studios.

Writers were beginning to feel the squeeze. They suspected that they were being shorted on royalties and residuals, and on their share of profits from the home-video market. At the same time, what was then called New Media—content on the web and for mobile devices—which wasn’t covered under the union contract, was starting to eat into their overall cut. In November 2007, the WGA went on strike. But writers were still making a fairly comfortable living, and others in the industry were not as supportive as they would come to be in 2023. “There was a sense of, ‘Why are you motherfuckers putting all the dry cleaners and caterers out of work?’ ” Rodman told me. “ ‘This is a picket line of millionaires against billionaires.’ ” The strike was ultimately undercut by dissent within the guild. The WGA agreed to an AMPTP offer that established the right to bargain over New Media and granted writers residuals for material rebroadcast online, but with no increase for DVDs.

When the strike was over, it was February 2008. The United States was three months into what would later be understood as the Great Recession. In an effort to stimulate the economy, the Federal Reserve had begun cutting interest rates in September, and over the following eighteen months it provided financial institutions with more than $7.7 trillion in capital. In late 2008, the Fed reduced the interest rate to almost zero. With piles of cash and cheap credit in hand, asset-management companies and private-equity firms set out for the frontiers of various U.S. industries. Over the next decade, three asset-management companies—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—would take over American business, becoming the largest shareholders of 88 percent of the S&P 500, the roughly five hundred biggest public U.S. companies. Private-equity firms—distinguished by their intent to sell the properties they acquire—would eventually be the backing for at least 7 percent of American jobs.

To these speculators, Hollywood looked like a gold mine: the studios and entertainment corporations were ripe with redundancies and inefficiencies to be axed—costs to be cut, parts to be sold, profits to be diverted to shareholders, executives, and new, often unrelated ventures. And thanks to the deregulation of the preceding decades, the industry was wide open. Financial institutions could snatch up or take over large portions of companies in any area of the business; they could even acquire or substantially invest in groups in competition with one another—and they did, creating types of soft monopoly. Bets were even placed against the traditional industry as a whole, in the form of investments in Netflix, which promised to disrupt and dominate at-home viewing. Today the Big Three asset-management firms hold the largest stakes in most rival companies in media and entertainment. As of the end of last year, Vanguard, for example, owned the largest stake in Disney, Netflix, Comcast, Apple, and Warner Bros. Discovery. It holds a substantial share of Amazon and Paramount Global. By 2010, private-equity companies had acquired MGM, Miramax, and AMC Theatres, and had scooped up portions of Hulu and DreamWorks. Private equity now has its hands in Univision, Lionsgate, Skydance, and more.

The flood of cash from Wall Street compounded the monopolization under way, accelerating mergers and acquisitions, and transforming already massive entities into behemoths. Between 2009 and 2019, Disney, for example, purchased Marvel, Lucasfilm, and 21st Century Fox. Comcast purchased NBCUniversal, DreamWorks Animation, and Sky. And the financial firms set about extracting and multiplying short-term profits. Andrew deWaard, a scholar of the political economy of media, has found that the use of dividends, stock buybacks, and corporate venture capital, all of which siphon revenue away from reinvestment in a business and its workforce, exploded in entertainment companies between 2008 and 2023. Comcast, for instance, which through its subsidiaries owns more than ten TV networks and studios, paid out more than $3.2 billion in dividends and stock buybacks in 2008. In 2022, that number topped $18 billion.

The studios, now beholden to much larger companies and financial institutions, became subject to oversight focused on short-term horizons. This summer, I spoke with the head of a film and TV studio purchased by a private-equity firm in recent years. “It used to be there were these big, crusty, old legacy companies that had a longer-term view,” he said, “that could absorb losses, and could take risks. But now everything is driven by quarterly results. The only thing that matters is the next board meeting. You don’t make any decisions that have long-term benefits. You’re always just thinking about, ‘How do I meet my numbers?’ ” Efficiency and risk avoidance began to run the game.

In the years following the recession, there was, as Howard Rodman put it, “a slow erosion” in feature-film writers’ ability to earn a living. To the new bosses, the quantity of money that studios had been spending on developing screenplays—many of which would never be made—was obvious fat to be cut, and in the late Aughts, executives increasingly began offering one-step deals, guaranteeing only one round of pay for one round of work. Writers, hoping to make it past Go, began doing much more labor—multiple steps of development—for what was ostensibly one step of the process. In separate interviews, Dana Stevens, writer of The Woman King, and Robin Swicord described the change using exactly the same words: “Free work was encoded.” So was safe material. In an effort to anticipate what a studio would green-light, writers incorporated feedback from producers and junior executives, constructing what became known as producer’s drafts. As Rodman explained it: “Your producer says to you, ‘I love your script. It’s a great first draft. But I know what the studio wants. This isn’t it. So I need you to just make this protagonist more likable, and blah, blah, blah.’ And you do it.”

At the same time, the fees that writers could charge for their work were being pushed down. Talent agents, who had previously advocated for their writers to make as much money as possible, were now employed by much larger companies that derived their revenue from a variety of other sources and controlled the market for writer representation. By 2019, the major Hollywood agencies had been consolidated into an oligopoly of four companies that controlled more than 75 percent of WGA writers’ earnings. And in the 2010s, high finance reached the agencies: by 2014, private equity had acquired Creative Artists Agency and William Morris Endeavor, and the latter had purchased IMG. Meeting benchmarks legible to the new bosses—deals actually made, projects off the ground—pushed agents to function more like producers, and writers began hearing that their asking prices were too high.

Executives, meanwhile, increasingly believed that they’d found their best bet in “IP”: preexisting intellectual property—familiar stories, characters, and products—that could be milled for scripts. As an associate producer of a successful Aughts IP-driven franchise told me, IP is “sort of a hedge.” There’s some knowledge of the consumer’s interest, he said. “There’s a sort of dry run for the story.” Screenwriter Zack Stentz, who co-wrote the 2011 movies Thor and X-Men: First Class, told me, “It’s a way to take risk out of the equation as much as possible.”

Brancato, who himself found work on Catwoman and two movies in the Terminator franchise in the early Aughts, told me that by the middle of the decade, no one wanted original scripts. IP had proved extremely valuable on the international market—increasingly important as domestic box-office growth stagnated over the course of the Aughts and 2010s—and it began to make up a greater and greater share of studio output. According to the media historian Shawna Kidman, franchise movies had accounted for around 25 percent of all studios’ wide-release features in 2000; in 2017 they made up more than 64 percent.

The shift to IP further tipped the scales of power. Multiple writers I spoke with said that selecting preexisting characters and cinematic worlds gave executives a type of psychic edge, allowing them to claim a degree of creative credit. And as IP took over, the perceived authority of writers diminished. Julie Bush, a writer-producer for the Apple TV+ limited series Manhunt, told me, “Executives get to feel like the author of the work, even though they have a screenwriter, like me, basically create a story out of whole cloth.” At the same time, the biggest IP success story, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, by far the highest-earning franchise of all time, pioneered a production apparatus in which writers were often separated from the conception and creation of a movie’s overall story. “Working on these big franchises is a little bit like being a stonemason on a medieval cathedral,” Stentz told me. “I can point toward this little corner, or this arch, and say, That was me.” Within this system, writers have sometimes been withheld basic information, such as the arc of a project. Joanna Robinson, co-author of the book MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios, told me that the writers for WandaVision, a Marvel show for Disney+, had to craft almost the entirety of the series’ single season without knowing where their work was ultimately supposed to arrive: the ending remained undetermined, because executives had not yet decided what other stories they might spin off from the show. Marvel also began to use so many writers for each project that it became difficult to determine who was responsible for a given idea. Multiple writers who worked on Guardians of the Galaxy, The Incredible Hulk, The Avengers, and Thor: Ragnarok have forced WGA arbitration with the company to recoup the credits and earnings that they believe they’re due.

Marvel’s practices have been widely emulated, especially for franchise productions. “Every other studio with big tentpole movies has tried to imitate the Marvel model,” Stentz told me, including “throwing waves of writers at the same project.” “In some cases,” he said, “they’ve gone even further, by convening entire writers’ rooms”—a standard practice only in television. Both the Avatar sequels (one of which is not yet out) and Terminator: Dark Fate were developed this way, he said.

“When there’s high-profile IP involved,” Brancato told me, “writers tend to be treated as disposable.” “Everybody’s feeling fucked over,” he said. “The general sense is that you’re an absolutely fungible widget, and they don’t any longer take you seriously. It’s so broken. I mean, really, it is fucking broken.”

The post-recession flood of cash and credit played out very differently in the world of television: for years, creative workers considered it an incredible boon. It opened the industry to new writers, new subjects, and powered an era that actually seemed defined by risk-taking.

Netflix had convinced Wall Street that its value could be measured by subscriber growth, rather than short-term profit, and the streamers that came soon after it adopted the same model. The streaming ecosystem was built on a wager: high subscriber numbers would translate to large market shares, and eventually, profit. Under this strategy, an enormous amount of money could be spent on shows that might or might not work: more shows meant more opportunities to catch new subscribers. Producers and writers for streamers were able to put ratings aside, which at first seemed to be a luxury. Netflix paid writers large fees up front, and guaranteed that an entire season of a show would be produced. By the mid-2010s, the sheer quantity of series across the new platforms—what’s known as “Peak TV”—opened opportunities for unusually offbeat projects (see BoJack Horseman, a cartoon for adults about an equine has-been sitcom star), and substantially more shows created by women and writers of color. In 2009, across cable, broadcast, and streaming, 189 original scripted shows aired or released new episodes; in 2016, that number was 496. In 2022, it was 849.

The need for writers was enormous. But thanks in part to the cultural success of the new era, supply soon overshot demand. For those who beat out the competition, the work became much less steady than it had been in the pre-streaming era. According to insiders, in the past, writers for a series had usually been employed for around eight months, crafting long seasons and staying on board through a show’s production. Junior writers often went to the sets where their shows were made and learned how to take a story from the page to the screen—how to talk to actors, how to stay within budget, how to take a studio’s notes—setting them up to become showrunners. Now, in an innovation called mini-rooms, reportedly first ventured by cable channels such as AMC and Starz, fewer writers were employed for each series and for much shorter periods—usually eight to ten weeks but as little as four. The weekly pay still put most other work to shame: between 2020 and 2023, a staff writer in a ten-week mini-room made at least $5,000 a week. But getting staffed for multiple rooms in a year was a challenge at best. Residual payments—which at the time did not account for a show’s success among viewers—were often tiny. One writer, who ran a show for Apple TV+ in 2020 and 2021, told me that his residuals were “near zero.” Justin Boyd, who around the same time wrote for both Netflix and AMC, said that his network residuals were roughly double what they were for the streaming platform.

Writers in the new mini-room system were often dismissed before their series went to production, which meant that they rarely got the opportunity to go to set and weren’t getting the skills they needed to advance. Showrunners were left responsible for all writing-related tasks when these rooms shut down. “It broke a lot of showrunners,” the A-list film and TV writer told me. “Physically, mentally, financially. It also ruined a lot of shows.”

The price of entry for working in Hollywood had been high for a long time: unpaid internships, low-paid assistant jobs. But now the path beyond the entry level was increasingly unclear. Jason Grote, who was a staff writer on Mad Men and who came to TV from playwriting, told me, “It became like a hobby for people, or something more like theater—you had your other day jobs or you had a trust fund.” Brenden Gallagher, a TV writer a decade in, said, “There are periods of time where I work at the Apple Store. I’ve worked doing data entry, I’ve worked doing research, I’ve worked doing copywriting.” Since he’d started in the business in 2014, in his mid-twenties, he’d never had more than eight months at a time when he didn’t need a source of income from outside the industry.

In the end, the precarity created by this new regime seems to have had a disastrous effect on efforts to diversify writers’ rooms. “There was this feeling,” the head of the midsize studio told me that day at Soho House, “during the last ten years or so, of, ‘Oh, we need to get more people of color in writers’ rooms.’ ” But what you get now, he said, is the black or Latino person who went to Harvard. “They’re getting the shot, but you don’t actually see a widening of the aperture to include people who grew up poor, maybe went to a state school or not even, and are just really talented. That has not happened at all.” To the extent that this was better than no change, he said, “Writers’ rooms are more diverse just in time for there not to be any writers’ rooms anymore.”

By the end of the 2010s, it was clear that something had to give or the industry would be facing a dearth of trained talent. “The Sopranos does not exist without David Chase having worked in television for almost thirty years,” Blake Masters, a writer-producer and creator of the Showtime series Brotherhood, told me. “Because The Sopranos really could not be written by somebody unless they understood everything about television, and hated all of it.” Grote said much the same thing: “Prestige TV wasn’t new blood coming into Hollywood as much as it was a lot of veterans that were never able to tell these types of stories, who were suddenly able to cut through.”

Netflix, the other streamers, and the networks weren’t just destabilizing the careers of individual writers: they were stealing from the industry’s future. But things were once again worse than they seemed. The streamers, which would soon employ about half of TV-series writers, were thoroughly speculative ventures, and they were set to expand and contract with the whims of the market.

In April 2022, Netflix told investors that it had lost two hundred thousand subscribers in the first quarter of the year. It expected to lose two million users in the next three months. Within days, its stock price fell by 35 percent. By September, it was down 60 percent. By November, the share price of Warner Bros. Discovery, the parent company of Max, had dropped by 61 percent; Paramount, by 49; Disney, by 44; and Comcast, by 38. Meanwhile, tensions between writers and executives were rising, and by the time the WGA’s board of directors was preparing for its triennial negotiations with the AMPTP, in the spring of 2023, they knew they were in for a fight.

The strike was called on May Day. In July, the actors guild, SAG-AFTRA, also struck, turning up the pressure on the AMPTP, and in late September, the studios and writers made a deal. In October, just days after the new contract was ratified, I spoke with Adam Conover, writer, creator, and star of truTV’s Adam Ruins Everything and a member of the 2023 WGA negotiating committee. The AMPTP had been shortsighted, he told me, locked in an old view of their labor force. “They didn’t realize that they did their job too well,” he said. “Workers actually got pushed out, actually got their wages cut.” The studios’ own systems had already forced many writers to take second and third jobs; the workers were not anywhere near as dependent on industry pay as they had been in the past. And they were furious. Compared with the stoppage in 2007 and 2008, one producer told me, “this felt more like scorched earth.” Many writers I talked to during the strike spoke of the executives with a mix of anger and disbelief. Boyd told me, “They cannot do what we do. And they hate us for it.” “I don’t think the studios had any reckoning,” Rodman said, “of the solidarity and militancy that their own greed created in the people who create their wealth.”

In the end, that solidarity succeeded in establishing a new streaming-residuals model—based on numbers of views—minimum staffing requirements and lengths of employment for TV writers’ rooms, and at least two rounds of guaranteed work for feature screenplays. The union had also forced streamers to release some viewership data, and had established that AI could not be given writing credit for anything: a human author would have to be involved and paid, regardless of AI output.

But as the dust has settled, it has become clear that there are several significant problems with the new agreement. The writers’-room staffing rules kick in only if a showrunner decides to bring on help at the start of a deal; otherwise, they can write a season on their own. It would often benefit them to go the latter route—budgets, after all, are shrinking—and studios would likely prefer this. One writer told me that by the start of 2024, he’d already seen showrunners use the loophole. As for the data-sharing agreement, a closer look reveals it to be, as deWaard put it, “very limited, and very fragile.” The studios will share viewership information with a limited number of WGA administrators for high-budget shows. The guild can then release that information only in a summary form, which, in the words of the contract, aggregates the data “on an overall industry level.” The guild cannot share any information at all on the performance of individual shows. A WGA representative told me that there would be no secondary process for writers to obtain that data.

The threshold for receiving the viewership-based streaming residuals is also incredibly high: a show must be viewed by at least 20 percent of a platform’s domestic subscribers “in the first 90 days of release, or in the first 90 days in any subsequent exhibition year.” As Bloomberg reported in November, fewer than 5 percent of the original shows that streamed on Netflix in 2022 would have met this benchmark. “I am not impressed,” the A-list writer told me in January. Entry-level TV staffing, where more and more writers are getting stuck, “is still a subsistence-level job,” he said. “It’s a job for rich kids.”

Conover said that the most important facts were that guild leadership had kept members unified and that a new streaming-residuals structure was now in place; they could fight to raise the rates during the next round of negotiations, in 2026. “Once something is a number on a piece of paper,” he said, “you can do a lot with it.” The majority of writers I spoke with this winter said that it was too soon to tell what the impact of the new contract would be. A group almost as large said that the agreement did not address the fundamental problems in the business.

Brenden Gallagher, who echoed Conover’s belief that the union was well-positioned to gain more in 2026, put it this way: “My view is that there was a lot of wishful thinking about achieving this new middle class, based around, to paraphrase 30 Rock, making it 1997 again through science or magic. Will there be as big a working television-writer cohort that is making six figures a year consistently living in Los Angeles as there was from 1992 to 2021? No. That’s never going to come back.”

Since the end of the strike, the industry has continued to contract. “It’s a great shaking-out point,” the A-list writer told me. “A lot of people who are very smart are willing to say, ‘I don’t know what it is going to be in a year, but it ain’t going to be this.’ ” Barry Schwartz, a film and TV writer in the industry for almost two decades, told me that post-strike, mid-career writers are making “extremely conservative choices.” “People aren’t speccing,” he said—submitting uncontracted scripts—“and if they are, it’s not original stuff. People are chasing IP or waiting on an assignment.” And younger writers, he said, are keeping their heads down.

As for what types of TV and movies can get made by those who stick around, Kelvin Yu, creator and showrunner of the Disney+ series American Born Chinese, told me: “I think that there will be an industry move to the middle in terms of safer, four-quadrant TV.” (In L.A., a “four-quadrant” project is one that aims to appeal to all demographics.) “I think a lot of people,” he said, “who were disenfranchised or marginalized—their drink tickets are up.” Indeed, multiple writers and executives told me that following the strike, studio choices have skewed even more conservative than before. “It seems like buyers are much less adventurous,” one writer said. “Buyers are looking for Friends.”

There’s no reason to believe that this type of caution will pay off. The supposed sure shot of IP is currently misfiring: in 2023, Disney’s The Marvels fell more than $64 million short of breaking even, and its Indiana Jones sequel drastically underperformed. The Flash, for Warner Bros. Discovery, lost millions, and the company’s Shazam! Fury of the Gods flopped. (In the case of Barbie—the loudest exception—the writers, Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, were given extraordinary free rein.) As Zack Stentz put it, “Hollywood is based on giving audiences what they might not know. Any attempt to drive risk out of that process is sooner or later doomed to failure.” His words played off an old adage by the screenwriter William Goldman. “Nobody knows anything,” he wrote. “Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for certain what’s going to work.” But investments in the alchemy of the creative process do not perform well in quarterly reports.

The film and TV industry is now controlled by only four major companies, and it is shot through with incentives to devalue the actual production of film and television. What is to be done? The most direct solution would be government intervention. If it wanted to, a presidential administration could enforce existing antitrust law, break up the conglomerates, and begin to pull entertainment companies loose from asset-management firms. It could regulate the use of financial tools, as deWaard has suggested; it could rein in private equity. The government could also increase competition directly by funding more public film and television. It could establish a universal basic income for artists and writers.

None of this is likely to happen. The entertainment and finance industries spend enormous sums lobbying both parties to maintain deregulation and prioritize the private sector. Writers will have to fight the studios again, but for more sweeping reforms. One change in particular has the potential to flip the power structure of the industry on its head: writers could demand to own complete copyright for the stories they create. They currently have something called “separated rights,” which allow a writer to use a script and its characters for limited purposes. But if they were to retain complete copyright, they would have vastly more leverage. Nearly every writer I spoke with seemed to believe that this would present a conflict with the way the union functions. This point is complicated and debatable, but Shawna Kidman and the legal expert Catherine Fisk—both preeminent scholars of copyright and media—told me that the greater challenge is Hollywood’s structure. The business is currently built around studio ownership. While Kidman found the idea of writer ownership infeasible, Fisk said it was possible, though it would be extremely difficult. Pushing for copyright would essentially mean going to war with the studios. But if things continue on their current path, writers may have to weigh such hazards against the prospect of the end of their profession. Or, they could leave it all behind.