Previously relegated to the dustbin of media history, the vinyl LP has undergone a revival during the past decade to once again become the best selling physical format for recorded music today.

Where barely one million new vinyl albums were sold in the United States in 2006, that figure has grown every year since, soaring to just over 49 million units in 2023. One in every 15 vinyl albums sold last year — approximately seven per cent of all sales (more than three million units) — were by Taylor Swift.

This is a global media comeback story. It is so significant the BBC recently reported that after a 30-year absence Britain’s Office of National Statistics has placed vinyl records back into the basket of goods it uses for tracking consumer pricing and measuring inflation.

(Josh Greenberg), Author provided (no reuse)

How is it that a media format as clunky, costly and fragile as vinyl would become so popular in an age of ubiquitous digital content? How is it that of all forms of recorded music, vinyl is the first to return to dominance from a state of near extinction? Why is it that an artist like Taylor Swift, whose core fan base is more familiar with companies like Apple or Spotify than high-end record turntables made by Thorens or VPI, would be the biggest selling artist of vinyl music?

There is no single reason behind this vinyl revival. One thing is clear, however: the massive growth in demand is a marketing triumph that is being driven by promotional culture. Old media is new again, vinyl is vintage and advertisers are adept at repackaging the past and selling it back to us for profit in the present.

Read more:

Gen Xers, millennials and even some Gen Zs choose vinyl & drive record sales up

From apocalyptic thrillers like Leave the World Behind to period music dramas like the criminally underrated The Get Down, and popular TV shows situated in the present — like Hijack, Suits, Transparent and Bosch — the presence of turntables and vinyl collections in their respective set designs delight vintage hi-fi enthusiasts and vinyl nerds. Vinyl albums and retro stereo gear have also appeared in ads for companies like IKEA, Whole Foods, Beck’s beer and Durex condoms.

Saturated in nostalgia

As these examples illustrate, today’s pop culture mediascape is saturated in nostalgia. Media companies, brands, marketers and even artists themselves are skilled at turning our longing for the past into desire in the present that can be satiated with consumer goods. We immerse ourselves in reconstructions of bygone eras and enact the sociocultural imaginaries of earlier times by latching to their products and incorporating them into our everyday lives.

Beyond the culture shaping influence of the promotion industries, there are also compelling sociological reasons for why vinyl is back in such a big way.

As a media sociologist I’m compelled to think about how seeking, acquiring, collecting and displaying one’s music collection — and one’s vinyl collection, in particular — are sociocultural activities that enable the creation and expression of identity.

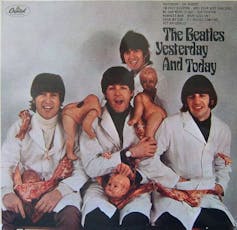

(Robert Whitaker)

One doesn’t simply become a vinyl collector automatically. The process of becoming a collector is a communicative phenomenon requiring the enactment of various ritual ordeals that are performed to convey authority, expertise and specialized knowledge about the distinctions between first pressings and reissues, the best techniques for cleaning and maintaining one’s collection, the backstory behind The Beatles infamous “butcher cover” artwork on their 1966 studio album Yesterday and Today, and other issues.

Collecting records is a form of identity

Considered in this way, our record collections (no matter how voluminous or sparse, rare or mainstream) and how we talk about them both shape and are shaped by the identity cocoons that form how we see ourselves and how we want others to see us.

For many audiophiles — those who prioritize sound quality, the provenance of sound recordings and the science of sound reproduction above all else — vinyl is considered an essential medium because of its allegedly superior sonic properties.

(AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

A clean pressing of my favourite Herbie Hancock album played through a quality hi-fi system arguably offers a warmer, fuller, more transparent reproduction of the original studio performance than can be provided by a CD or streaming service.

Although digitally encoded music delivers technically better signal-to-noise ratio and frequency response, vinyl provides a distinctive aural feel for the music and a qualitatively different (some might say superior) sonic experience.

So much of the music we listen to now is transmitted from the cloud to apps on our mobile devices via compressed audio files that sound flat and unexpressive. There is something to be said about listening to a format like vinyl that, by contrast, sounds more open, dynamic and alive.

We live in a ‘hyperaesthetic culture’

The anthropologist David Howes argues that we live in an increasingly dynamic and competitive sensory environment, what he calls a “hyperaesthetic culture,” where the promotion of consumer goods — from cookies to pizza, mobile phones and, yes, even vinyl records — continually appeal to how we see, touch, hear, taste and smell our way through the world.

Beyond acoustic properties and claims to sonic superiority then, what makes vinyl so important is its polysensorial character — not only what we hear from the encoded microgrooves through playback, but also how vinyl looks, feels and even smells.

Avid record collectors often say that the questions of sound aside, an album’s material elements are its most distinctive quality — specifically the liner notes that we open, read, pass around to friends, or the enclosed artwork that we may display on our walls.

Our favourite record stores are also sensorially rich in the odours of PVC, cardboard, mould, fast food and other scents that have been baked into the shop’s physical setting and its unique history. The vinyl sensorium constitutes and shapes our core memories and experiences of acquiring, learning and talking about music that is fundamentally different from other recorded music technologies or places of acquisition.

(AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Vinyl is also a good example of what the musicologist Mark Katz calls technostalgia. Memories are imperfect representations of reality that get distorted with the passage of time. Events of the past are remembered in the present through refractions in old photographs, video recordings and the stories we tell ourselves around dinner tables, reunions and family gatherings.

Do I actually remember sitting on the shag rug in our wood-panelled family room floor, listening to my dad’s Beatles records with an over-sized pair of Realistic headphones wrapped uncomfortably over my ears? Or have I merely reconstituted that memory based on a weathered Polaroid that froze this fleeting moment in time?

Repackaged memories

Memories are not permanent or fixed. They are, rather, constructs that are entangled with the media technologies that shape the events and rhythms of our lives. Perhaps this is why they are so easily repackaged and sold back to us.

When I play a copy of Iron Maiden’s best-selling 1982 album The Number of the Beast (the first record I ever bought with my own money), I experience more than just a recording of the band’s breakthrough studio performance.

I also recall that unseasonably warm October day in 1982 when I rode my bike from our home to the local record store. If I close my eyes, I can still feel the sun on my face and the wind in my hair, just as I feel the pulsing of the music in my chest as it pumped over the store sound system, and the smell of the place, how awkward and out of place I felt, and how quickly those feelings vanished once I got home, skinned the album from its shrink wrap, unsheathed the vinyl from its protective sleeve and dropped the needle onto the album’s outer groove: click, pop, hiss.

Vinyl’s unlikely comeback story is linked therefore to a combination of marketing and promotion, claims of superior sound, the medium’s polysensorial character and how it evokes nostalgia to construct and reconstitute memory.

A highly social practice

It is also important because for many collectors, listening to records is a highly social and cultural practice that connects past to present and locates individuals within both real and imagined communities.

“Deep listening,” a normally solitary activity that leads one to seek a recording’s precise sonic details, can be obtained by experimenting with playback settings, equipment setup and other audible techniques to solicit an album’s intended expression of sound.

In contrast, collective listening occurs not alone but in the company of others. I think here of my close-knit group of friends who gather every few months for shared meals, drinks and conversation, listening to music, passing around album jackets and liner notes, talking about what we most like about a given artist or recording.

Collective listening activities like this are not new, of course, but have arguably become more vital as we move further from a period of enforced pandemic isolation to becoming social again.

Vinyl also mediates passage of time in unique ways. I think about the acquisition of used albums or entire collections that once belonged to other enthusiasts may combine elements of both deep and collective listening.

A recent collection I purchased had been dutifully cared for by its original owner, who not only maintained the vinyl’s physical purity and durability, but also inserted small handwritten notes into the sleeve detailing his impressions about the album’s production and engineering, favourite tracks, the dates on which he listened to them and technical comments describing how he configured his stereo to obtain the fullest expression of the album’s sound.

Reading those listening notes as I played his old records that were now mine, it’s remarkable how connected I felt in the present to a total stranger from the past.

(Kanina Holmes), Author provided (no reuse)

A premature death

In 1984, Rolling Stone contributing writer Fred Goodman prematurely published vinyl’s obituary when he wrote “Record Industry Preparing to Bury the Vinyl LP” just as CD technology and cassette use were becoming the dominant media of choice for popular music fans.

Though vinyl sales plummeted in the two decades that followed, the format’s storied comeback and meteoric rise in popularity over the past 15 years are in some respects confounding.

For one thing, we live in a time of digital ephemera where rapid and inexpensive access to media content is both possible and reasonably affordable. We both can see and hear media content, yet it also vanishes to the cloud and remains elusive. Moreover, the digital mediascape generates its own problems and consequences that help explain why vinyl has become so vital again.

As my record-collecting teenage daughter explains, vinyl’s appeal is that it takes up space and forces you to look and listen. Indeed, one of the common side effects of our current age of digital everything is a growing desire for more engagement and interactivity with the media content, tools and technologies we use in our lives. We have an urge to sense our environment and to hear, see, feel and smell all of the beauty (and also noise) that surrounds us.