Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has secured the colorful San Andrés Tetepilco codices. These Aztec documents from the late 16th and early 17th centuries recount the founding of San Andrés Tetepilico and chart Tenochitlan’s wider history. Though these artifacts belonged to an anonymous family for generations, INAH just announced that it were able to raise 9.5 million pesos ($570,000) from a group of entrepreneurs to purchase the relics. There are only 500 known Mesoamerican codices in the world, and 200 of them are in Mexico’s National Library of Anthropology and History (BNAH).

The saga began in 2009, when a colleague told historian María Castañeda de la Paz that they knew a collector with manuscripts of interest. Castañeda de la Paz visited Mexico City’s upscale Coyoacán neighborhood, and was shocked by what a spokesperson for the family showed her via a monitor. “Documents about the history of Tenochtitlan are very rare,” she told El País.

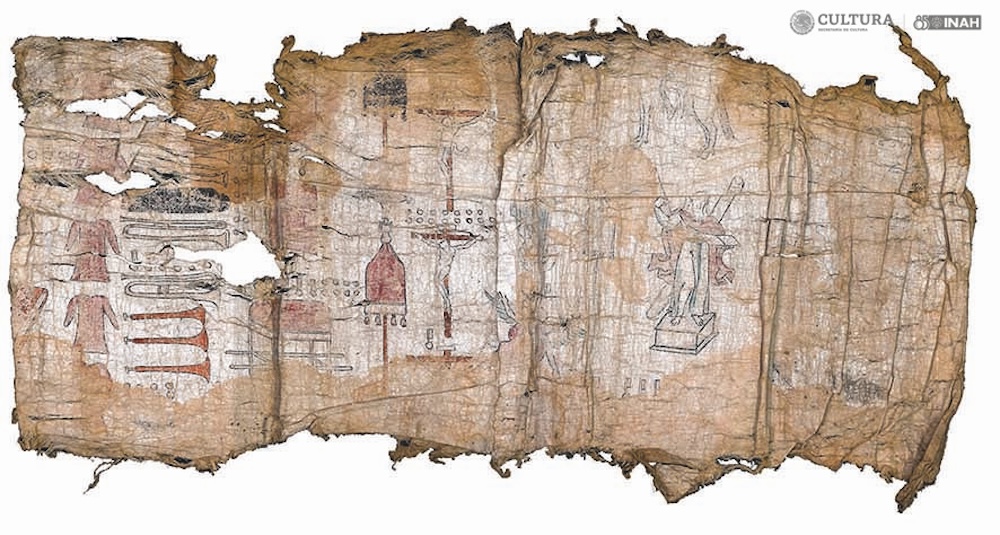

The codice recounting the founding of Tetepilco. ©SC, INAH, BNAH

Castañeda de la Paz struggled staying in touch with the family, much less convincing them to hand the codices over. Such treasures do well on the black market, but this family felt more like stewards. Castañeda de la Paz showed color copies of the codices to BNAH head Baltazar Brito Guadarrama, who helped eventually procure the relics.

Mexican law states that historical assets hailing from the Spanish Empire’s viceroyalty period (1535–1821) may remain in private collections so long as they stay in the country. These codices illustrate a society in flux, combining the classic style of Aztec scribes with artistic innovations like shading and perspective—as well as text written in Nahuatl and using the European alphabet. All three codices were created on amate paper with gesso and natural dyes from insects, indigo, charcoal, and more.

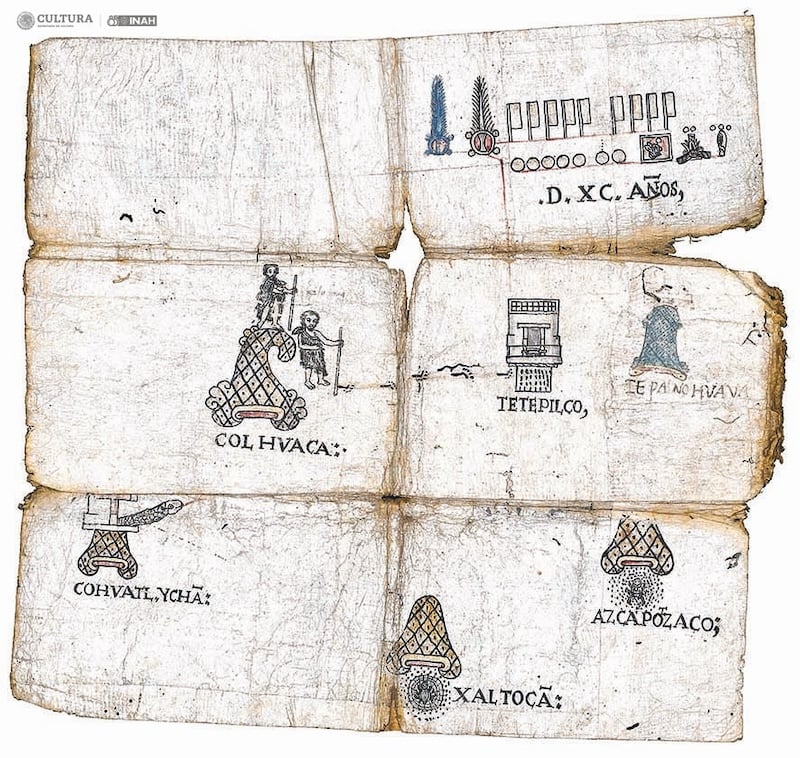

San Andrés Tetepilco, one of the original 15 settlements of present-day Iztapalapa, was situated on the southeast side of Mexico City—formerly Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital. The first codex documents Tetepilco’s founding, mentioning the names and locations of several other known Aztec settlements. Jornada reports that infrared imaging revealed this otherwise unassuming codice is a palimpsest, with pre-Hispanic scenes beneath its visible layer. Meanwhile, historians have made out through the ancient inventory’s poor condition that the church of Tetepilco held clergy outfits, instruments, and banners.

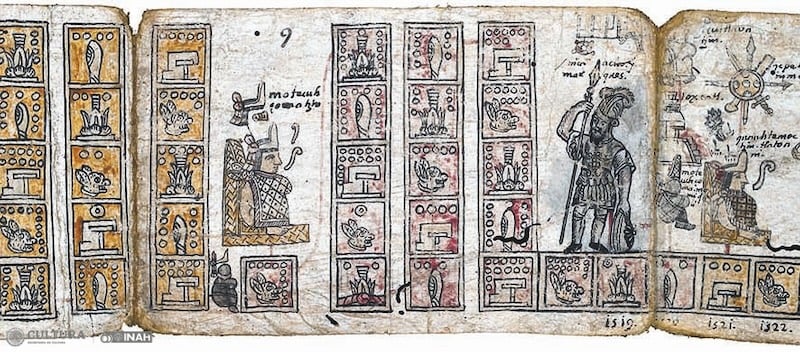

A section of the Tetepilco Strip. ©SC, INAH, BNAH

The third codex, however, is the real gem, retelling the history of Tenochtitlan in four acts, a continuation of the famed Boturini Codex. The strip of 20 folded screen sheets “narrates the history of Tenochtitlan through four themes,” INAH explained, including “the founding of the city, in 1300 (which implies a gap of 25 years); the record of the lords who governed it in pre-Hispanic times; the arrival of the Spanish, in 1519, and the viceregal period, until 1611.” Castañeda de la Paz has likened this codex to a Rembrandt or Velázquez based on its beauty.

Overall, INAH compares this acquisition with the authentication of the Mayan Codex of Mexico six years ago. These codices will now reside in BNAH, where they’ll undergo further study and conservation. Researchers also promise to publish them digitally and physically for the public.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.