After years of growing his increasingly passionate fanbase with independent and digital-first novels, Alexis Hall achieved mainstream popularity—and hit the bestseller list—in 2020 with the witty London-set rom-com, Boyfriend Material. The equally successful Rosaline Palmer Takes the Cake followed a year later, and now the British author is conquering historical romance with A Lady for a Duke.

Being presumed dead after fighting in the Battle of Waterloo gave Viola Carroll the chance to live as the woman she has always been, but it came at the cost of her best friend. Two years later, Justin de Vere, the Duke of Gracewood, is still devastated by Viola’s supposed death and has become a recluse. Viola travels to his estate to try and help him, even though doing so could destroy the new life she’s built. We talked to Hall about the thorny questions that come with writing about queer characters in a historical setting and why he’s such a prolific author. (A Lady for a Duke is his second release in 2022, with two more to come!)

It’s been a busy few years! Do you ever sleep?

Well, I don’t sleep much, and I have no social life. I kind of joke about this, but it’s genuinely not sustainable for me. Basically, because the market changed quite a lot and quite quickly in terms of how receptive people are to queer romance, this is sort of the first time in my career that these kinds of opportunities have been possible for me. So I did what any reasonably neurotic person would have done and said yes to everything. Which does mean my life is temporarily on hold. I’m hoping to get to a more sensible pace in a year or two.

Are you a fastidious organizer when it comes to drafting or is it a more chaotic process?

This feels like a nonanswer but sort of both? The answer I usually give to the plotter versus pantser question is that it fails to take into account that pretty much all books go through multiple drafts and you need to use different techniques at different parts of the process. Like, I’ll usually have an outline for the first draft, but then the first draft is itself kind of the outline for the second draft. And there have been books that have looked, in their final form, quite similar to how they looked when they started, but there are others that are almost unrecognizable. So I guess I’m organized when I need to be organized and chaotic when I need to be chaotic. To be fair, I’m sometimes also chaotic when I need to be organized.

“It was important to me . . . that neither the text nor really anyone in the text should meaningfully question that Viola is a woman.”

A Lady for a Duke takes place after the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, which Viola fought in and after which she was presumed dead. Why did you choose to make Waterloo the pivotal turning point in her life?

Firstly, and most simply, Waterloo is a big, iconic, central feature of the Regency, and I wanted to engage with it in a meaningful way. It was kind of one of the most devastating military conflicts that Europe had ever seen, so that feels . . . significant? Otherwise, it would be like setting a book in 1916 and never mentioning the First World War.

The other reason is a bit more narratively focused. It was important to me from very early on in the conception of the book that neither the text nor really anyone in the text should meaningfully question that Viola is a woman because, frankly, I don’t think anyone benefits from fiction legitimizing that particular “debate.” And so that meant I needed Viola to have transitioned and to be comfortable in her identity from the moment she arrived on page. In that context, Waterloo gives depth to the life she lived and the choices she made in the past, while providing a source of conflict between her and Gracewood that’s not related to her gender identity.

Viola’s first interactions with Justin are some of the most emotionally fraught moments in the entire book. How did you ensure the poignancy of these moments without slowing down the pace?

I always feel bad about these crafty kinds of questions because I feel like people are expecting a more insightful answer than I actually have. I mean, the short answer is “I don’t know, and I suspect some readers will think I didn’t.”

But I think some of it, partially, is just trusting my audience. One of the hardest (and most freeing) things about writing genre romance is that people recognize that the emotions are the plot. I mean, you can have other plots as well, but it’s not like you’re ever going to get a romance reader saying, “Nothing happened in this book except some people got together, where are the explosions?”

How is writing about queer love in the Regency era different from writing a contemporary queer romance?

In some respects, it isn’t. The philosophy I tend to take about writing in a historical setting is to keep clear sight of the fact that I’m still a modern writer writing a modern book for a modern audience. And how far I’ll steer into that will vary quite a lot. For example, my other Regency series is unabashedly, absurdly modern in pretty much all of its sensibilities, and some readers don’t like that, and that’s fine. But I don’t think there’s anything intrinsically wrong with writing historical fiction like A Knight’s Tale instead of The Lion in Winter.

That said, I think there are some decisions you have to make consciously that, in contemporary fiction, you’re allowed to make unconsciously. Readers often have quite specific expectations about how being LGBTQ should be presented in a historical setting, and those aren’t always expectations I’m going to agree with or play into.

I think one of the more subtle questions it’s important to address in writing a queer love story in a historical environment is whether you are going to use modern perceptions of identity or, as best you can, historical perceptions of identity. On the one hand, it is correct to say that relationships and experiences that we would today attach specific labels to have always existed. But, on the other hand, neither those labels nor the often quite complex set of assumptions that go with those labels would have made sense to people in a historical setting.

My general take comes back to what I said about keeping in mind that I’m writing for a modern audience. It’s ultimately more important to me that my queer stories resonate with modern queer readers than it is for them to portray what I think a person at the time might actually have perceived their identity to be. Not least because that’s unknowable.

“One of the hardest (and most freeing) things about writing genre romance is that people recognize that the emotions are the plot.”

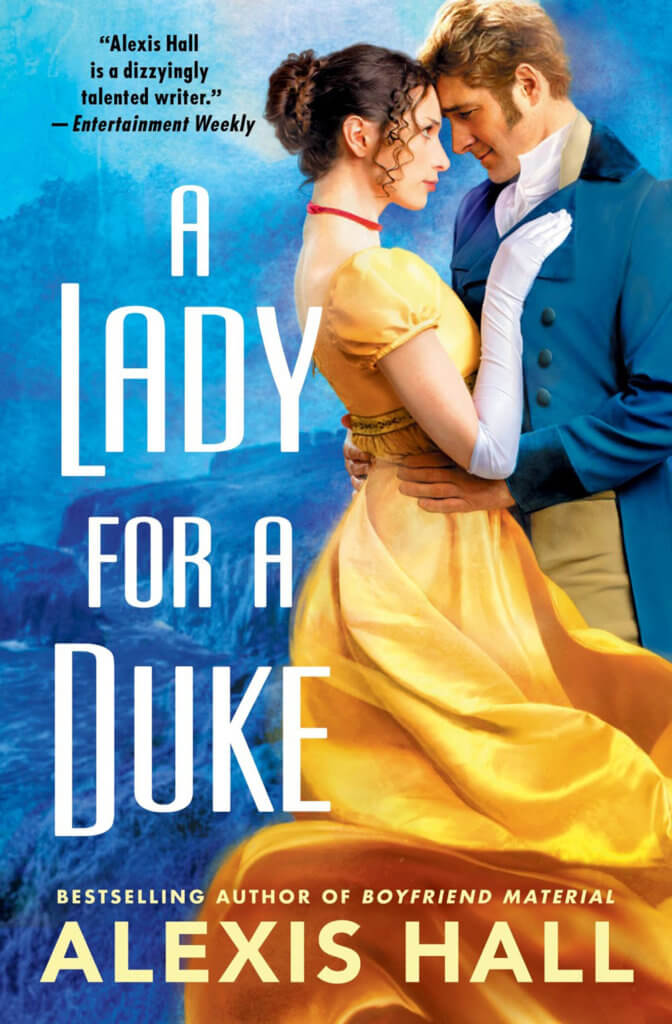

Both the cover model for Viola and the audiobook narrator of A Lady for a Duke are trans women. Why was it important to you to involve trans women in the process of bringing this book to life? And how did you feel the first time you saw its gorgeous cover?

Who can represent whom and in what media is a complex question that doesn’t necessarily have clear generalizable answers. For example, I’m not sure I could readily articulate why I felt it was important to have a trans woman narrating Viola (or why I tend to feel that it’s important to have POC voice actors narrating books with POC protagonists) but haven’t felt so strongly about having voice actors who match the identities of my gay or bisexual characters. I’m also deeply aware that this isn’t a topic that I have authority to pontificate on, and in many ways I am just kind of guided by instinct. For what it’s worth, I do have another book (The Affair of the Mysterious Letter) in which the trans male narrator was portrayed by a cis man in the audiobook because, at the time, I couldn’t find a British trans man to do it. Ultimately I think that was an acceptable second best, and the voice actor did a great job, but I think I’d have felt bad if I could have had a trans voice actor for A Lady for a Duke but gave the job to a cis person anyway.

One of the things I wanted to do with A Lady for a Duke (and I’m far from the first person to do it) is to contribute to the normalization of trans people within romance in general and historical romance in particular. And perhaps I’m wrong, but I hope having Violet looking gorgeous as Viola on the cover and Kay Eluvian doing a fantastic job narrating the audiobook helps to communicate that trans people belong here as much as cis people do.

And yes, the cover is perfect and I love it.

Tell us about the research you did for this book. What did you learn that surprised you?

The first thing I’d say is that it’s worth remembering that the Regency is an incredibly tiny bit of history both spatially and temporally. Like, not only did it cover just nine years of actual time (1811–1820), but if we’re talking about the specific community that people are usually talking about when they’re talking about the Regency, we’re talking about the 10,000 richest people in England. And, in fact, if you narrow it down to the subset of people that historical romance tends to focus on (which is to say, dukes and people who directly interacted with dukes), you’re getting into the low hundreds.

On top of that, there’s the broader issue that I’ve loosely touched on already, which is that the language we use to describe LGBTQ identities and experiences in the present day only really applies to the present day. So, for example, we do know a certain amount about molly houses, which were brothels/social clubs in the late 18th century (which, honestly, were kind of fading out by the Regency) where men would go to have sex with each other, sometimes cross-dress and sometimes do sham weddings and even sham births. But none of that can necessarily be assumed to map onto any specific identity as we understand it today.

“I don’t think there’s anything intrinsically wrong with writing historical fiction like A Knight’s Tale instead of The Lion in Winter.”

Similarly, there have always been people who have lived as a gender that is not the gender they were assigned at birth (although, obviously, the only ones we know about are the ones who were outed, either during their lives or post-mortem), but we can’t necessarily know how those individuals understood their identities. It gets particularly complex when you’re talking about people who were assigned female at birth and lived as men. Hannah Snell, for example, dressed as a man to fight in a war but afterward told her own story in a way that very strongly framed her as a woman who had dressed as a man to fight in a war. But there are also people like Dr. James Barry who lived as men during their lifetimes and made it very clear that they wanted to be thought of, known and remembered as men after their deaths.

An ongoing problem with queer history in general and trans history in particular is you can’t prove how a person really thought about themselves, and mainstream culture tends to demand a very high burden of proof. Dr. James Barry is a really good example. Here we have a man who lived as a man, explicitly stated he was a man and wanted to be remembered as a man, but most of his biographies present him as a woman who cross-dressed to access privileged male spheres. And while I’m not a historian, as a human being my personal feeling is that if someone says they’re a man, you should, like, believe them.

What was the most challenging aspect of writing A Lady for a Duke?

In any romance book, you need an emotional nadir of some kind, because otherwise the journey toward the happily ever after can feel like it lacks stakes or tension. This usually happens at 70% into the story, but that didn’t feel right for this book.

I knew the main source of conflict was going to be what happened at Waterloo, but the idea of having that hanging over the book, the characters and the reader for 200 to 300 pages was just super grim. Viola and Gracewood also have a lot to work through both personally and socially, and I didn’t think I’d be able to squoosh that into the last third of the book. All of which meant that I actually hit the emotional nadir at about (spoiler) 30% or 40%. And because of that change in structure, it took some finessing to make sure the rest of the book still felt like it had something to say and the characters had somewhere to go.

What have you been reading lately?

I recently read a phenomenal contemporary rom-com called The Romantic Agenda by Claire Kann. It’s kind of a riff on My Best Friend’s Wedding, but it centralizes two asexual characters who are navigating their complicated relationship with each other while falling in love with other people. The heroine, Joy, is an absolute joy. And I think it’s just one of the most romantic books I’ve ever read.

I also loved The Stand-In by Lily Chu, another contemporary rom-com. This one has a zany “Oh, you look exactly like a famous film star” premise, but it’s actually incredibly grounded and tender, exploring the importance of all kinds of relationships, not just romantic ones.

Oh, and Siren Queen by Nghi Vo is breathtakingly good. It’s a magical, dark fairy-tale take on pre-code Hollywood about a queer Asian American film star who makes a name for herself playing monsters, since she won’t faint, do an accent or take a maid role. It’s incredibly intense but, at its heart, exquisitely kind. One of those books you feel genuinely humbled to have read.